Natasha Christia, non-affiliated curator, writer and educator.

Lukas Birk, FERNWEH: A Man’s Journey, a series of exhibitions and a book.

FERNWEH: A Man’s Journey was originally conceived as a mutating touring exhibition:

Lukas Birk: Travelogue Sammlung Istanbul. Noks Independent Art Space. Istanbul, October 13–November 5, 2018.

Lukas Birk: Sammlung-bis jetzt. Galerie Hollenstein, Lustenau (Austria), September 21–October 28, 2018.

Travelogue Sammlung by Lukas Birk. Transformart Gallery-Belgrade Photomonth, April 2018.

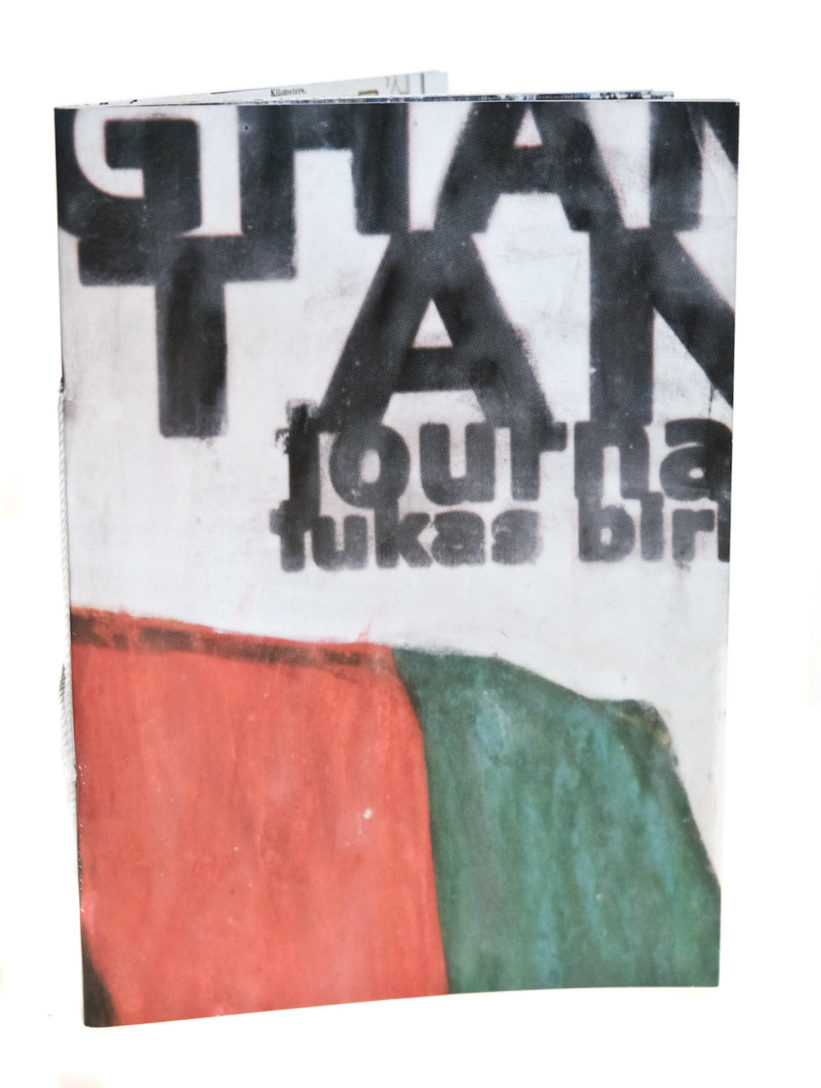

And a BOOK *

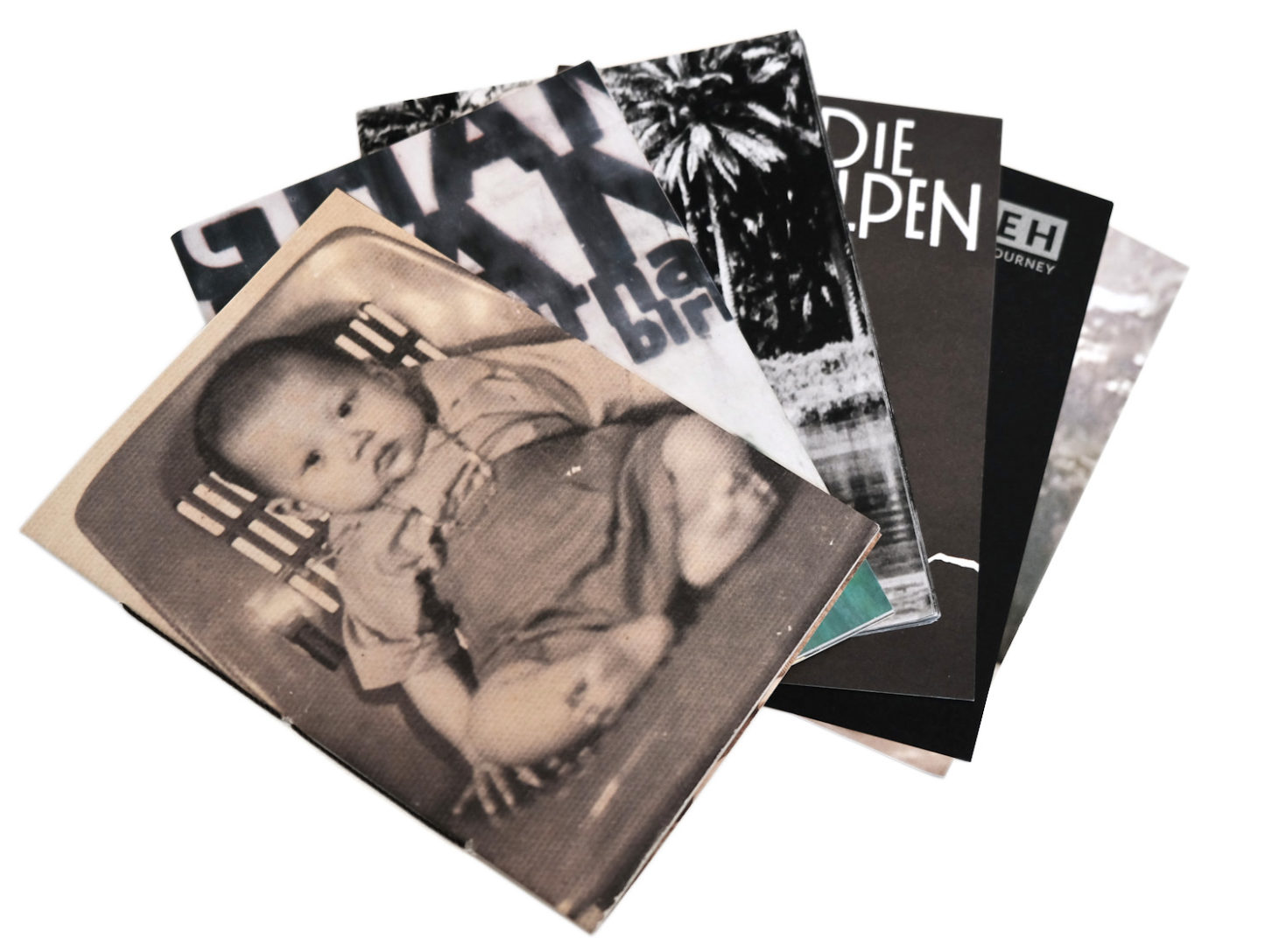

FERNWEH: A Man’s Journey. Edited by Natasha Christia & Lukas Birk. Fraglich Publishing 2018.

Six Brochures. 20x15cm. The publication emerged as the outcome of the curatorial project. With an introduction by Natasha Christia.

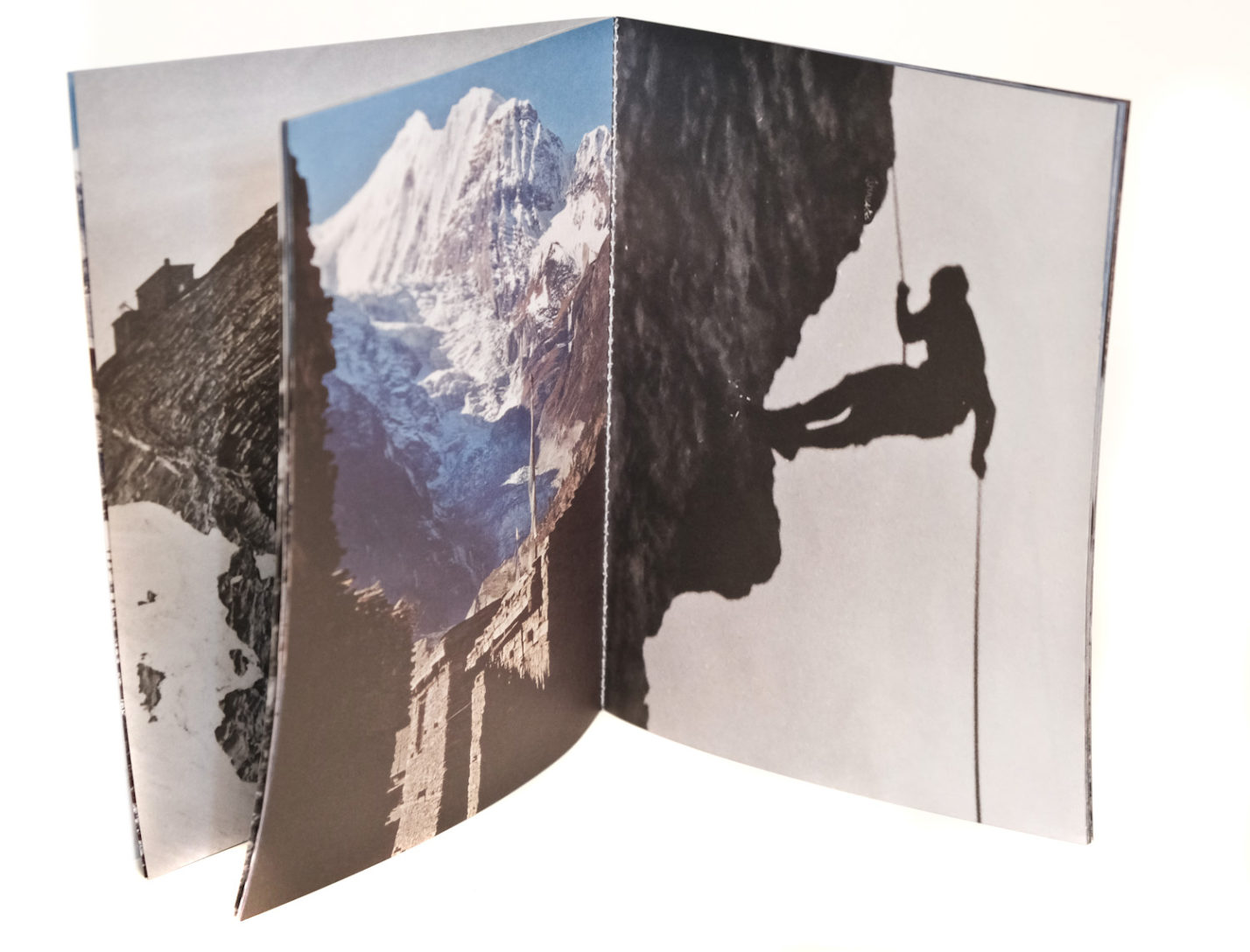

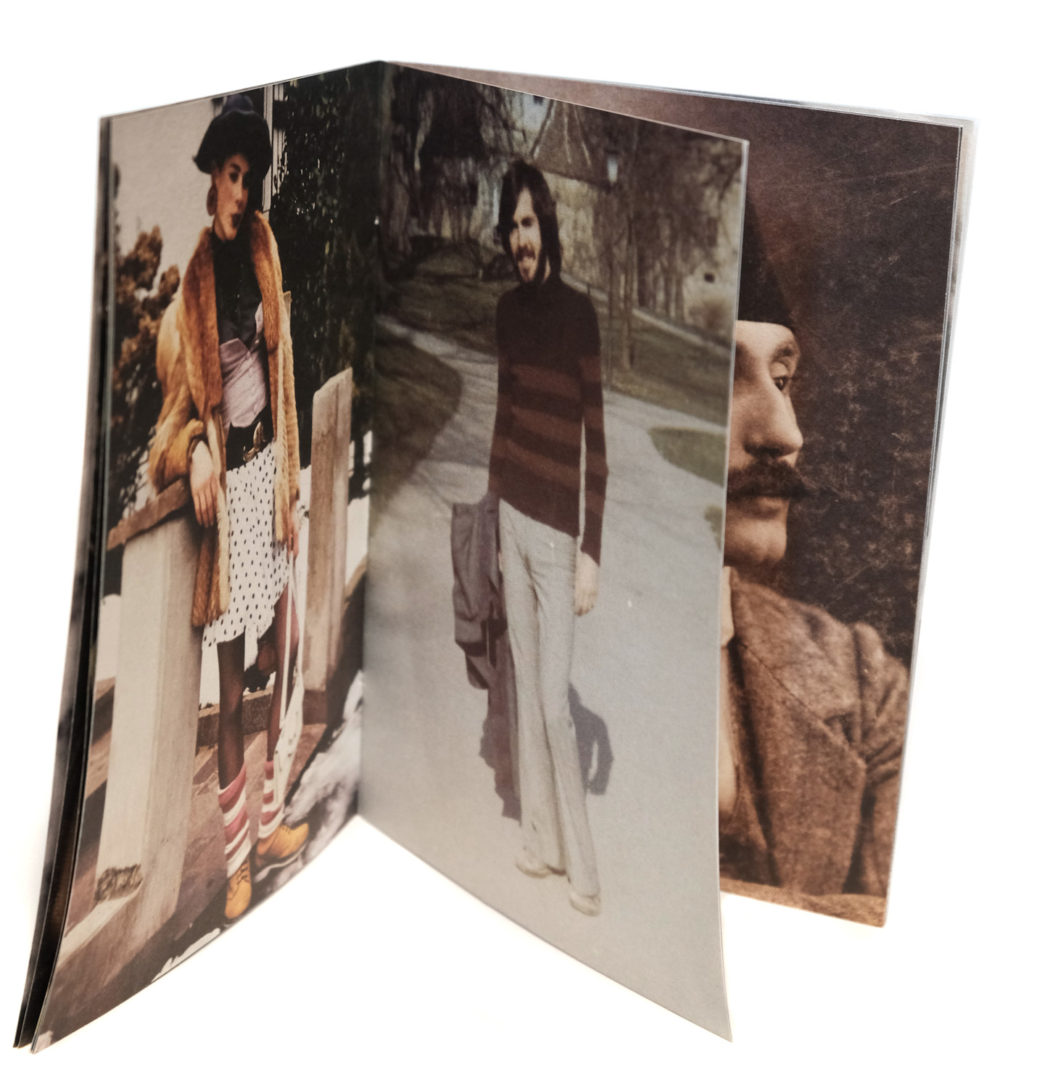

In FERNWEH, storyteller, artist and collector Lukas Birk repurposes his extensive personal collection, comprised of visual memoirs of journeys that have taken place over seven decades in his homeland of Austria, the Balkans, the Middle East and South Asia. From vernacular to fine art photography and from the intimacy of the family album to ruthless public exposure, the product of this operation is a novel archival assemblage, both real and imaginary at heart. A remix of sorts, FERNWEH unwraps the lifetimes of three generations of men: Lukas’ grandfather Viktor Birk, who served as a soldier in the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany during World War II; his father Andreas Birk, a hippy traveller and adventurer of the 1970s and 80s; and finally, Lukas himself, a contemporary wanderer and artist. All of them shared a passion for travelling, the camera and the mountains.

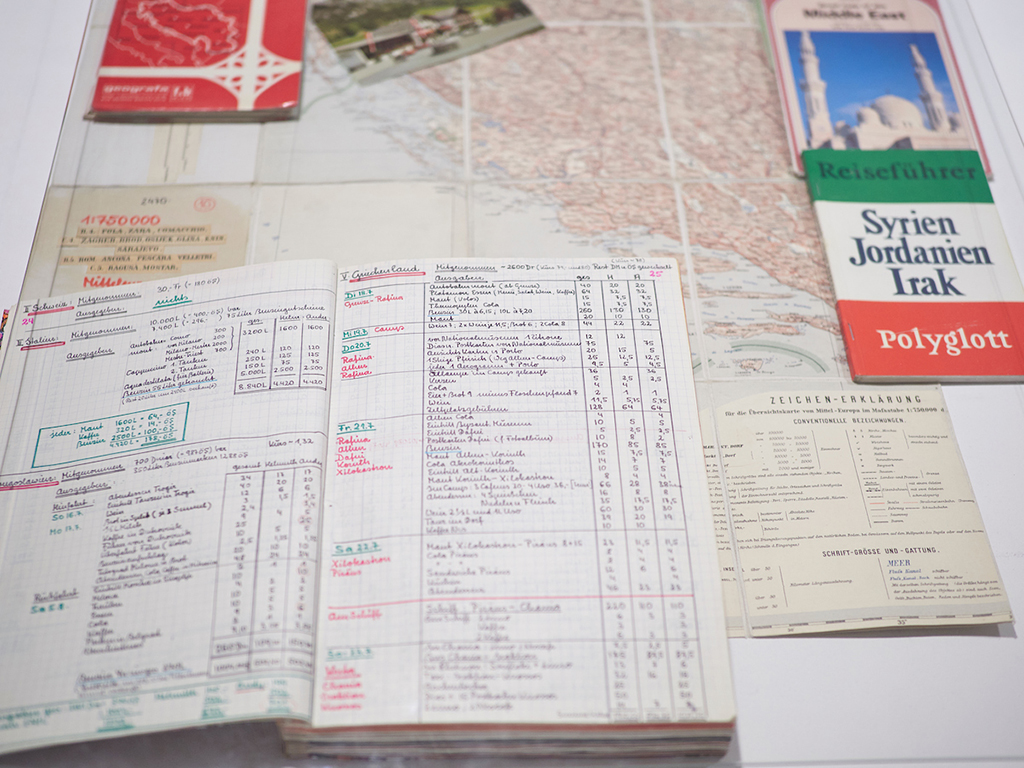

To bring this sophisticated albeit cryptic visual depository to life, Birk has referred both to his progenitors’ legacy and to his own history as an artist. Old travellers’ guides, maps and handcrafted Birk family photo albums of homeland mountain excursions and far-away road journeys coexist with materials from Lukas’ personal archive, such as prints, journals, travel memoirs, and portraits of anonymous men, all collected and/or produced between 1999 and 2017.

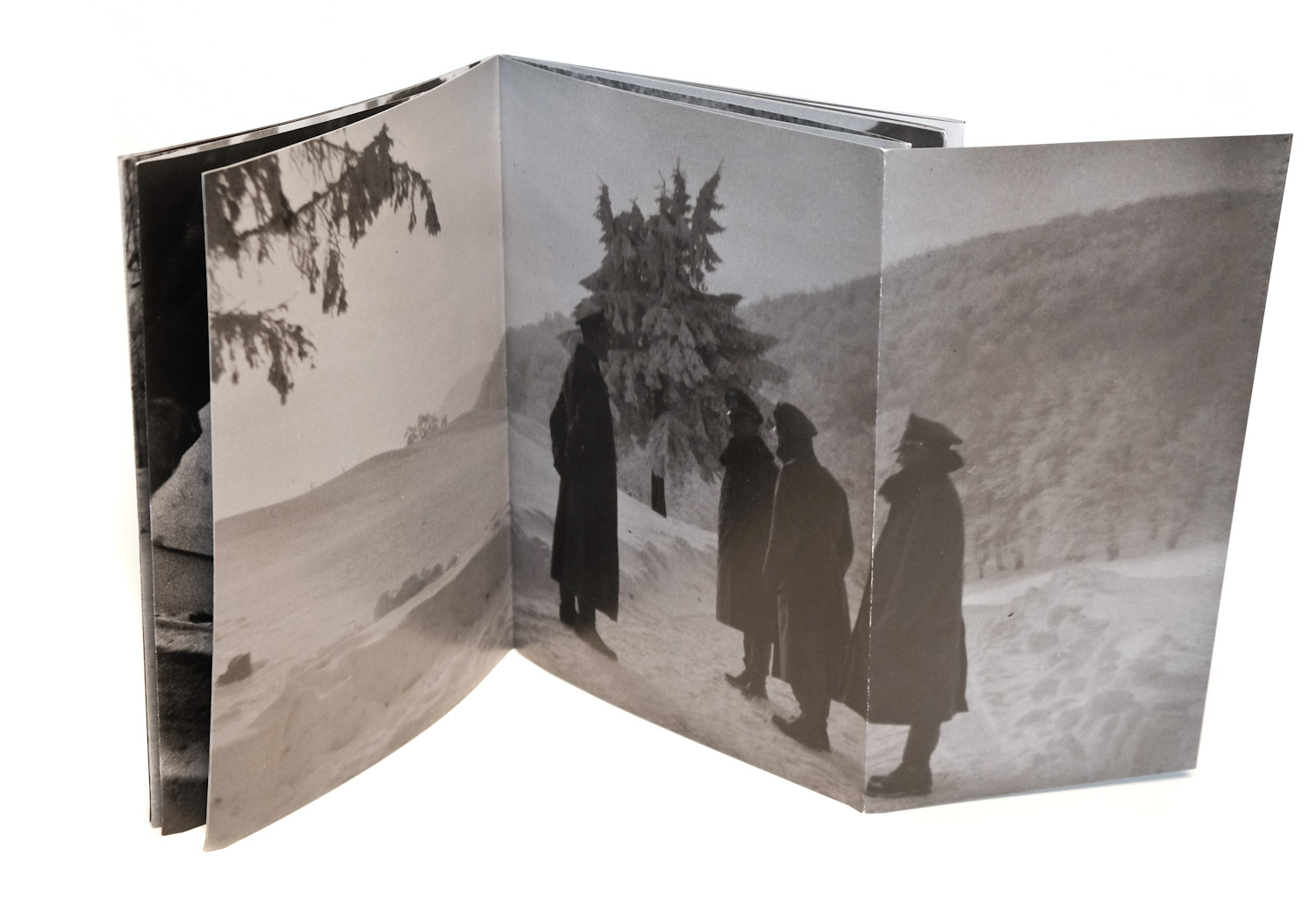

Some of Birk’s publications have provided the historiographical ground for the unfolding of the three timelines. 35 Bilder Krieg (2015) employs 35 negatives, found in an envelope, to reconstruct the route of soldier Viktor, Birk’s paternal grandfather, presumably in the Balkans, Paris and Greece during World War II, while Kafkanistan (2008) explores the world of present-day tourism while questioning the possibility of cultural identity assimilation in the conflict areas of Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. Perhaps the most significant material in the enriching and fictionalisation of the triple male plot is a series of altered books: Atlas (a 1973 Austrian school atlas); 3 Bitef 212 (a 1969 Belgrade Theatre Festival catalogue); and Berg, by Luis Trenker (1932). The practice of embedding extra elements within their pages, such as photographs, album spreads, documents and annotations – all paramount in the shaping both of Lukas’ family history and his own identity as a travelling voyeur – has permeated the mash-up spirit of the whole project.

On which fields of knowledge are you focused?

Curating lens-based contents: exhibitions, texts narratives.

What is the object of your research?

My research focuses on the exploration and reinvention of dominant narratives through a novel reading of archival collections, the intersection of photography, film and the photobook, and the dialogue between 20th century avant-garde photography and contemporary forms of expression often labelled as post-photography.

Could you identify some constants in your work?

Agency: Excavating, unveiling strata/layers of History’s individual and collective experience, re-reading/revisiting the medium’s grand narratives, comparing, relativizing, defamiliarizing due to my condition of being a “foreigner” and its derivatives Sehnsucht and Fremdweh – all these attitudes are nourished by my background in archaeology, history and my Hellenic homeland roots, where the weight of historical time is too present.

Recurrent attitudes: passion for literature and the historical myth, for narratives that address the utopia of putting oneself in the skin of the other side’s narrative.

How did you find out about Aby Warburg’s work? What interests you the most?

If I recall well, I discovered Aby Warburg some years ago during a correspondence I held with my colleague and friend Marco Paltrinieri from Discipula. We were exchanging ideas on a curatorial project that was formulated as an exercise of purposive discontinuity, (re)contextualization and speculation applied on a specific visual and textual body of work. The project is still unfulfilled, but Warburg’s Mnemosyne Bilder Atlas has occupied its place in our conversation.

What draws my attention to the Warburgean operation is the event of the serendipitous montage of ideas and objects it entails; its defense of a (seemingly) bare image and of (apparently) arbitrary associations that unearth the psychological tenors and attitudes of past times. I cannot help myself but relate his typological universe with Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project, August Sander’s Antlitz der Zeit, and Karl Blossfeldt`s Urformen del Kunst. All of them were German like the early 20th century cultural and media milieu that propelled their discourses. I am intrigued by this non-casual coincidence and by fact that their historical times had a similar transitional character to ours. But I also associate Warburg to André Malraux and his Imaginary Museum (I do think it would have been possible for Malraux to envision his ideal collection of artwork reproductions without Warburg; both share experiences like their fleeting passage to agitated colonial world). On a personal level, his Atlas panels draw me back to the plates of ancient vessel profiles that illustrated the archaeological publications I used to come across during my long study hours in the libraries of the Foreign Archaeological Schools in Athens. Archaeological research is Warburgean in tenor, since, when it comes to interpreting and reconstructing the scenarios of past societies and cultures, the classification of field acquired data is fundamental. Finally, I am drawn to this chimeric aspiration to manifest a world order through systems of images, but also to the possibility of becoming Warburg myself through the mental chains of experience and objects performed by my words in this paragraph.

How would you define an Atlas?

“The map is open and connectable in all of its dimensions; it is detachable, reversible, susceptible to possible modifications. It can be torn, reversed, adapted to any kind of mounting”. Gilles Deleuze-Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. 1988. 13.

For me an Atlas entails the notion of territory in literal and mental terms. It brings forward an intrinsic awareness of borders and historical time. An Atlas is not only what it shows, it is also the way it shows it. An Atlas requires that you draw with your hand a line to track and mark the path you are going to follow. Different atlases denote different colluding paths. All of them incite a constant confrontation with your limited knowledge resources, but also the effort to imagine the unknown/unfamiliar, and to memorize it, to make it yours. In this sense, the atlas is upon the eye and the will of the beholder. But it is also a reminder of our nexus with community (in some cases a liberating, in many others an oppressive condition). This cross operation of gazes, interpretations and past memories is its raison d’être. In terms of an intellectual operation, putting yourself into the position of the percipient implies that you are open to the journey/adventure, to coming across the other, and to embracing dialectics alongside uncertainty and unpredictability (in this sense, the Atlas appears so intrinsically connected with the contemporary condition). Each project I embark with an artist turns into an atlas. Before us arises a visual system of apparently innocent elements that trigger unexpected ambiguous associations and counter positions. By consenting to embark on this, we embrace voluntary displacements and revisions; we willingly dismantle and scrutinize identities, civic rights and systems of ideas, and happily and playfully or painfully re-enact them, in a mutual effort to map a horizon and to project anew the self and as something new.

Atlas as a conceptual, formal and mnemonic device; do you use it in your work?

In FERNNWEH, the Atlas appears first literally in the form of a 1973 Austrian school atlas of the Birk family which is repurposed by the artist. This school manual delimitates a personal territory of journeys – fulfilled or imagined – but also makes reemerge a historical territory with strong political and cultural connotations. Birk’s interventions reshape it as a new atlas, a new hybrid/contaminated surface of associations. They propel a performing and re-reading of journeys that are already undertaken; and by repeating them they convert them into something else. Then the atlas form shifts onto the wall. Besides the literal mapping of the journeys of the three male characters in the first part of the exhibition, the whole installation turns into a universal atlas of signifiers that by means of repetitions, citations of forms related to the pathos of journey, photography and masculinity invite the viewer to decodify and experience them anew. A visual dialectics is established through the montage of visual and textual elements, which, despite their apparent exoticism or disconnection, end up always anchored in the viewer’s personal and collective reminiscences: in Belgrade there were allusions to Balkan history and its collective imaginary, in Austria to the family’s and region’s past under National Socialism, in Istanbul to the local memories of tourism through vernacular photography. By displacing pictures and throwing them back into the arena of history, the narrative in FERNWEH expands further into a universal atlas of family stories and identity correspondences, reinforcing novel associations in the personal and collective memory. Amid its elaborate stratigraphy of collages, maps, recycled and new images, the three male protagonists and their storylines literally become one, merging with the lives of myriad others. A liquid amorphous identity arises and timelines are carved into one non-linear and multi-voiced narrative that breathes within a dusty archival folder of scattered memories. When it comes to the publication, its five booklets are employed as roadmaps of an a priori incomplete photographic memory, misconstrued by nature. They also operate as interconnected vessels of a shared experience, inviting the reader to step back and forth in time and engage with their documents according to their own visual and emotional resonances.

Do you know about the existence of Mnemotechnics?

Yes.

Which mnemonic system guides the organization of you’re the material related to Fernweh?

Since we did not develop this mnemonic system consciously, I would prefer to view it in retrospective. The three men and the timelines of the generations and historical times they represent, along their passion towards photography (the technological apparatus and its technological evolution) and towards the mountain (as a symbol of ambition and ascension), operate as the mnemonic devices of the project. The interconnections/montage and ultimate symbiosis of different temporalities, world visions and male perspectives cause the flattening of historical time within the narrative of both the space and the printed page. The three men coexist at the same age, grow up and experience the work in parallel. Though apparently simplistic, this comparative association of their lives resumes their century, and its dominant views and attitudes regarding masculinity, colonialism and artistic identity. Through this abolition of spatial and temporal references, a novel de-historicised interpretation of personal and collective memory emerges, wittily seeking to revisit notions and clichés such as the male iconology of adventure and ascension to success, the trappings of exoticism, the ‘Other’ as a Western construct, colonial encounters, folklore and the status of the artist.

Another mnemonic device in the project is the self-referential inclusion of the photographic apparatus as an event per se. Through its different technologies and applications (the photo-album, the slide, the analogue camera, the digital file, color, B&W), it anchors the narrative in historic time providing colorful resonances on predominant gazes – the male, the colonialist, the artistic.

Are there visual and emotional formulas (pathosformeln) in your this project?

The Pathosformeln of this project revolve around identity as fomented by photographic representation and reproduction in the 20th century. This is underpinned through Birk’s X=Y identities, a series of fake ID identity cards made out from the artist’s self-portraits, that explores the omnipresent importance of identification through an on-going performative assumption and crafting of different identities. Thanks to this project, whose origins were independent from the exhibition, we were able to track down next to the artist’s fascination with identities similar unconscious operations in the case of his father and grandfather, when it came to the performing of identity before the camera. Frontality, the apparent lack of pathos but also the rigid representation of masculinity and youth edified the agency of the three men photographers to perform themselves before the camera as explorers, travelers, artists, photographers and venerable citizens of their times. We complemented our assemblage with another series of photobooth portraits of men from Myanmar, Pakistan and India, that belong to Lukas’ travelogue archive. Putting all these visual elements together enabled us to connect multiple life threads across different continents, and cultural and historical environments. Above all, it enabled us to observe and expose the re-enactment of masculinity that takes place in them through a series of humble visual signifier that perpetuate masculinity in different cultures, among them the moustache and the authoritative male uniform. This fusion of faces restored the unconscious quest for a chimeric ID-card identity that seems foregone. It also fragmented our perception of the protagonists: the Western and white privileged male traveller is no longer situated in the central point of a central perspective but is rendered unrecognisable in order to partake with the ‘other(s)’ in a common tale.

In this work, do you identify formal or conceptual recurrences such as repetitions and disruption, distance and proximity, identity and migration, conflict and colonization?

As mentioned before, there is a series of pattern repetitions in the project. First of all, there are the portraits of men coming from different sources – the three protagonists during their childhood, youth, older years, alongside men from archival portraits from Middle East and southeast Asia. Similarities in expressions and faces manifest themselves involuntarily, causing identity to dissolve. You cannot tell who is who; all is everyone, and everybody looks at everyone. The re-enactment of the colonial gaze creates fissures in a seemingly Eurocentric narrative stepped on the three generations of a wealthy Austrian family who explore the world, while it ironically undermines any pretension for exoticism and undermines the image of the male traveler and the colonial gaze. A similar operation of displacement takes place in other signifiers, such as, for instance, the mountain. For the Austrian traveler, the Alps embody the Heimweh, the craving for homeland. The Alps are projected onto any mountain – Afghanistan, Nepali peaks, all the mountains displayed through photographic reproductions in the exhibition are the Alps. Distance and proximity are cancelled. The elegy views of the homeland peaks, dissolved in super 8 film footage, become unfamiliar and menacing when mediated by the burden of the historical past of the region -in the aesthetic form there is a collision of historic reading, a rupture. These constant migrations end up reorganizing mentally identities and values. The mental horizon of these three generations and the visual culture that revolves around them dissolves. There are no frontiers, limits, or hierarchy, just the multiple manifestations of a concern – the moral duality of their century perhaps, oscillating between Heimweh and Fernweh.

In your work, what is the balance between image and text?

I envision image and text as two equal agents in the dissemination of meaning in the project. Birk’s publications, the Birk family albums and various travelogue records provide the historiographical ground for the unfolding of the timelines of the three protagonists. Alongside them, significant a role in the fictionalisation of the triple male plot play a series of altered books: Atlas (a 1973 Austrian school atlas); 3 Bitef 212 (a 1969 Belgrade Theatre Festival catalogue); and Berg, by Luis Trenker (1932). The installation experience is stepped on the act of the visitor reading/flipping through these performative cultural objects (which are display horizontally), and of confronting the wall install anew. In the case of the altered books, the embedding of extra elements on their pages, such as photographs, album spreads, documents and hand-written annotations by the artist, reinforces the mash-up spirit of the whole project. The apparently defunctionalised and defamiliarized contents of these repurposed books hinder a straightforward reading of the wall display when the viewer comes back to it. The whole exhibition invites to this cyclic reading and re-reading of images, objects, textual records and space narrative It encourages a rampant, open-ended dialectic condition that does not prioritise one over the other, neither images over books, nor the artist protagonist of the family saga narrative over the artist voyeur.

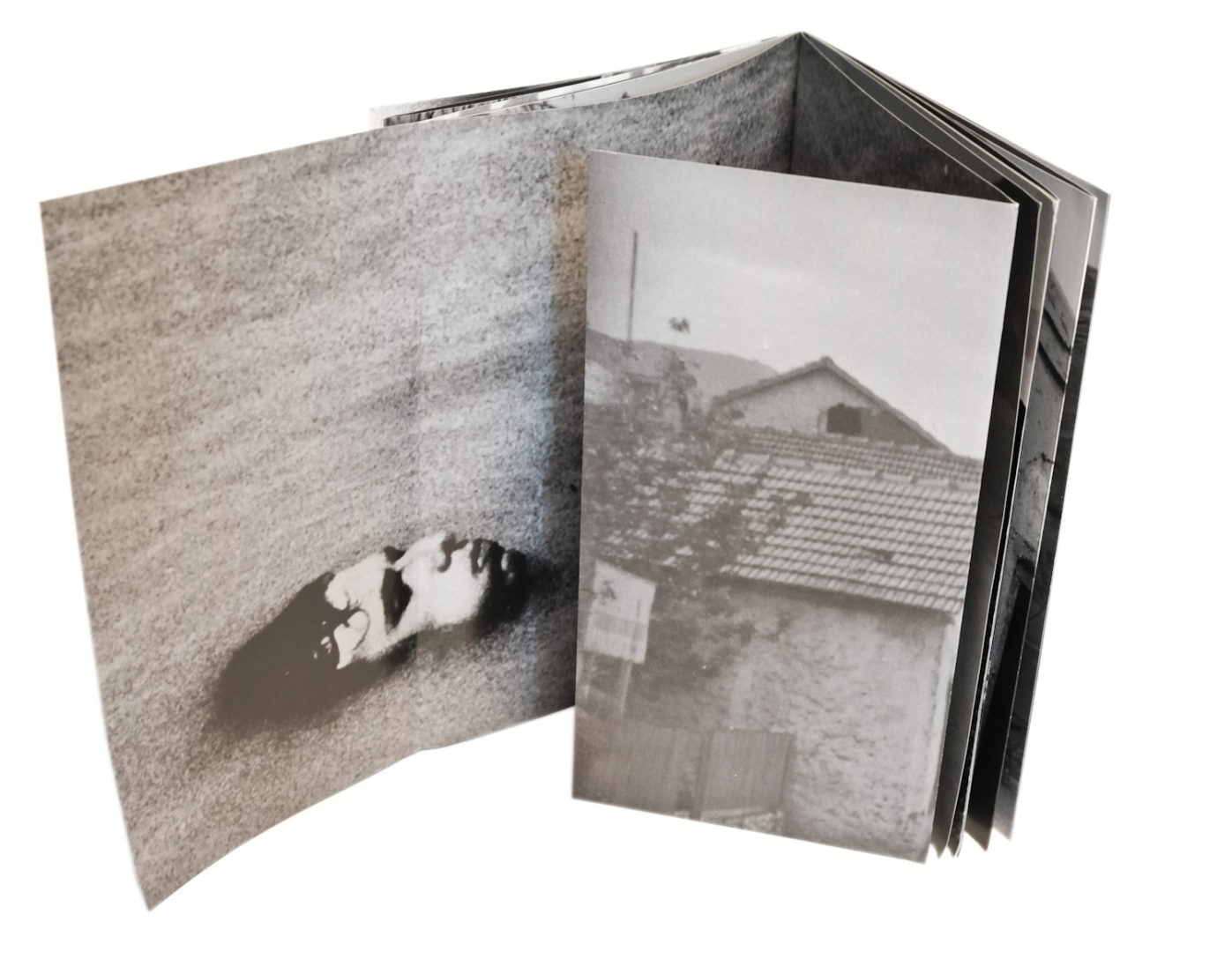

The publication is another story. The image is prevalent there. With its six brochures that respect typologies (Male Portraits; Narrative; Maps; Mountain; Texts), it is made more as loose atlas multiples. Even its production process, the fact that was printed in five different places of the world (Yangon, Istanbul, Bregenz, Istanbul) under completely different production regimes reflects this open attitude. The whole material is re-assembled here, it is thrown on the table for a new atlas to emerge. The reader starts repurposing the cards again, turning the familiar into unfamiliar again.

Thinking about Warburg’s ‘good neighborhood rule’, what are the books that underpin your project?

The books come from the ecosystem of our project. They insinuate migrations of function, contents and authorship.

35 Bilder Krieg (35 Pictures War). By Lukas Birk. Re-versioned copy by Lukas Birk, 2018.

Österreichischer Atlas für Höhere Schulen. Verlag Ed. Hölzl, 1973. Re-versioned copy by Lukas Birk, 2018.

3 bitef 212. September 69. Bitef Festival Guide, September 1969. Re-versioned copy by Lukas Birk. 2018.

Kafkanistan. By Lukas Birk & Sean Foley. Glitterati Incorporated, 2012.

Berge im Schnee. By Luis Trenker, Neufeld & Henuis Verlag. Berlin, 1932. Re-versioned copy by Lukas Birk, 2018.

House No 6. By Lukas Birk. Self-Published, 2017.

X=Y. Identities. Self-published, 2014 and 2015.

Rebirth Reverie. Journal by Lukas Birk. 2011. Mixed media, artist’s book.

Afghanistan Journal. Journal by Lukas Birk, 2012. Mixed media, artist’s book.

Photo Peshawar by Sean Foley & Lukas Birk. Mapin & Pix Publishing, New Delhi, 2018.

Burmese Photographers. By Lukas Birk. Goethe-Institut, Yangon 2018.

We were drawn here. By Lukas Birk & Moshtari Hilal. Limited edition-self published, 2016.

Studio Light. By Lukas Birk. Dummy 2016.

Studio Light in colour. By Lukas Birk. Dummy 2016.

Jänner-Juni 1972. Andreas Birk Photo Album, 1972.

Lukas 1982-1987. Photo album by Andreas Birk.

1953-1959. Family album by Viktor Birk.

Natasha Christia (Athens, 1976) holds a BA in Archaeology and History of Art (National Kapodistrian University of Athens), an MA in Modern Art and Film (University of Essex), and a Postgraduate Diploma on Publishing (University of Barcelona). From 2005 until 2014 she was the art director of KOWASA gallery in Barcelona and from 2009 until 2012 member of the research group Arqueologia del Punt de Vista. Natasha regularly contributes essays on photography criticism for international publications and artists. She was the guest editor of OjodePez magazine 41, Self Calling and guest-editor of The Book: on Endless Possibilities for the Read or die Publishing Fair 2015 in Barcelona. She was the artistic director of DocField Barcelona Documentary Photography Festival 2016 Europe: Lost in Translation. She has recently curated The Family of No Man (co-curated with Brad Feuerhelm for Arles Cosmos 2018), and You Are What You Eat, a group exhibition on food, identity politics and ideology for Krakow Photomonth 2019.