Tarek Elhaik, Anthropologist and film/video curator

The Incurable – image. Curating Post Mexican Film and Media Arts, published by Edinburgh University Press 2016

From the 1990s onwards the ‘ethnographic turn in contemporary art’ has generated intense dialogues between anthropologists, artists and curators. While ethnography has been both generously and problematically re-appropriated by the art world, curation has seldom caught the conceptual attention of anthropologists. Based on two years of participant-observation in Mexico City, I address this lacuna by examining a complex assemblage of inter-media practices, from experimental cinema and installations to curatorial collaborations. Taking cue from ongoing critiques of Mexicanist aesthetics, Gilles Deleuze’s Time-Image, and Warburg’s Surviving Image, I conceptualize curation less as an exhibition-oriented practice within a national culture, than as a pharmacological figure of care and mode of thought populated by what I call “incurable images.”

On which fields of knowledge are you focused?

Anthropology of Art, Anthropology of the Image, Aesthetic Anthropology, Philosophical Anthropology, Anthropology of the Contemporary

What is the object of your research?

My research focuses on inter-medial and trans-regional genealogies of thought through an inquiry into artists’ image-work and modes of thinking.

Could you identify some constants in your work?

Montage; Assemblage theory; the dialogue between art history, anthropology, and philosophy; the power of images; and the relationship between the “curatorial” and the “comparative.”

How did you find out about Aby Warburg’s work? What interests you the most?

I first encountered Warburg’s work through both his Kreuzlingen Lecture and George Didi-Huberman’s L’image Survivante. I find Warburg’s concepts of nachleben and pathos-formel very interesting insofar that they help me to think about 1) the afterlives of Ancient, Scholastic, and Modernist conceptual repertoires in contemporary art and thought; 2), the comparative method as a form of montage and mode of curation, 3) the relation between form, image, and affect that emerges in trans-regional and multi-sited research design.

How would you define an Atlas?

A surface on which the lives of images, forms and objects both undergo a radical transformation of their initial identities and correspond with one another to generate a pure difference.

Atlas as a conceptual, formal and mnemonic device; do you use it in your work?

Yes, I do, in two types of practices indirectly related to my academic work: radio programming and film curation. The concept of Atlas is particularly useful when I edit my radio show materials or when I program a film series for a contemporary art or cinema venue. Both practices require a movement between memory and matter, between infinity and finitude. Each of these radio shows and film programs is therefore the result of a process of re-composition of fragments (images, sounds, gestures, concepts, etc). Moreover, this mnemonic movement is also a question of health. For instance, the digital audio software I use to edit my radio shows is called Reaper. Its mode of operation uses practical and technical terms that evoke both pathos and memory. When I cut a media item or audio segment it is called a “split.” When I want to undo the split, the software also gives me the option to “heal” the cut. Something mysterious happens in between, like in an Atlas.

Do you know about the existence of Mnemotechnics?

Yes.

Which mnemonic system guides the organization of your material?

I am interested in resonances created through “affinities” (neither sameness nor radical alterity) encountered in the course of fieldwork. Rather than organize my material as fieldwork “data” I instead prefer to approach it as a “dynamogram” that gives me the diagnosis and pulse of a fieldwork “encounter” whose memory, in turn, dictates the form of my writing.

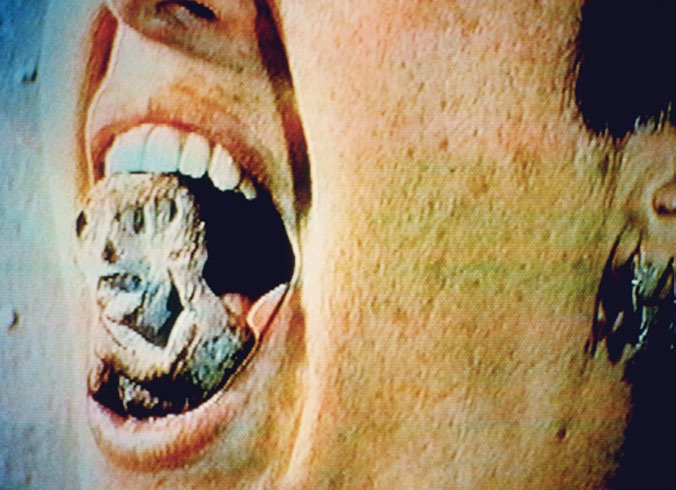

Are there visual and emotional formulas (pathosformeln) in your project?

Yes. An example is my description of the Mexican experimental film La Formula Secreta. (see Chapter 2 in my book The Incurable Image)

In your work, do you identify formal or conceptual recurrences such as repetitions and disruption, distance and proximity, identity and migration, conflict and colonization?

Yes, I do, and in both my first fieldwork in Mexico and my current work on the ‘nachleben’ of the intense scholastic debate between Aquinas and Averroes in contemporary art and new media theory. In Mexico, I was interested in the way my informants, mainly curators and artists, were reanimating Sergei Eisenstein’s Que Viva Mexico, as a strategy to bid farewell to that monument of the Mexican Vanguardia. For my second book project, I find various types of ruptures and continuities between the Averroist / Aristotelian concept of “cogitation” and the theoretical writings of conceptual artists, such as Adrian Piper, Giulio Paolini, and Mounir Fatmi.

In your work, what is the balance between image and text?

Images are the point of entry for almost everything I do, so there might be perhaps a bias towards them over words. However, I try to convey and express the sensible intensity of images in words and concepts, so the relationship between words and images is ultimately one of radical interconnectedness.

Thinking about Warburg’s ‘good neighborhood rule’, what are the books that underpin your project?

Hans Belting. An Anthropology of Images: Picture / Medium / Body. (Princeton University Press), 2011

Jorge Luis Borges. El Etnografo / The Anthropologist in In Praise of Darkness (Dutton), 1974, pp. 46-47.

George Didi-Huberman, L’image Survivante: Histoire de L’Art et Temps des Fantomes selon Aby Warburg. (Paris: Les Editions de

Minuit), 2002.

Gilles Deleuze. L’Image Temps. (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit), 1985.

Franz Boas. The Limitations of the Comparative Method in Anthropology, in Science, N. S., Vol. IV., No. 103, Pages 901-908,

December 18, 1896.

Walter Benjamin. Reflections on Radio in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, eds. Jennings, Doherty and Levin.

Harvard University Press, 2008, p. 391-407.

Glen Gould. Radio As Music in The Glenn Gould Reader, ed., Tim Page, Vintage Books, 1984.

Paul Rabinow. Unconsolable Contemporary: Observing Gerhard Richter (Duke University Press), 2018

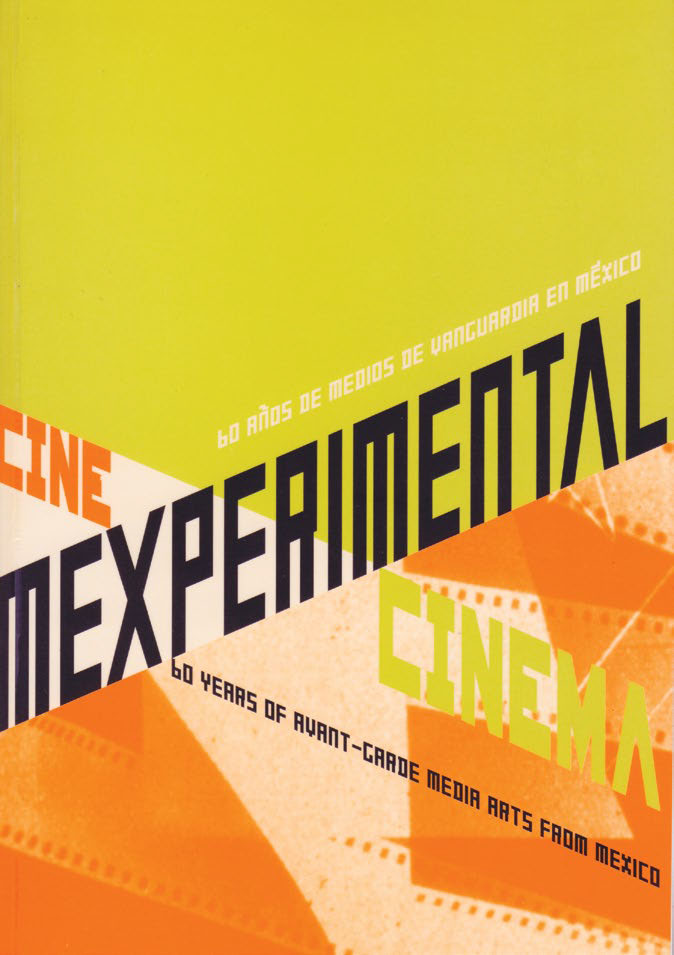

Tarek Elhaik is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Davis. His research is focused on aesthetic anthropology, inter-medial and trans-regional genealogies of thought; theories of the image; curatorial practice; and artists’ modes of thinking. He is the author of The Incurable-Image: Curating Post-Mexican Film and Media Arts (Edinburgh University Press, 2016), a book based on participant-observation in Mexico City’s contemporary art scene and intellectual life, and of Cogitations: Aesthetics and Anthropology (Routledge, 2021). Between 2014-2017 he was part of Ism Ism Ism: Experimental Cinema in Latin America, a collaborative team of researchers and platform hosted by the Los Angeles Film Forum and funded by the Getty Foundation’s PST initiative LA/LA. He is also the founder of AIL: the Anthropology of the Image Lab and the host of the radio show “Cogitations.”