Alena Alexandrova, cultural theorist and indipendent curator

Three exhibitions and a book in development

Capturing Metamorphosis, exhibition at the Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam, 2010

Hypothesis of a Lost Fragment, exhibition at YGREC, École nationale supérieure d’arts de Paris Cergy, 2015

Anarchic Infrastructures: Recasting the Archive, Displacing Chronologies, exhibition + symposium + now a book draft

There are two exhibitions I curated, which resonate with, and are inspired by Warburg’s approach. In the first one I looked at the role of motif of plasticity and metamorphosis as related to histories and concepts of image-making, and in the second one I explored the role of the figure of the missing piece.

Capturing Metamorphosis, exhibition at the Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam, 2010

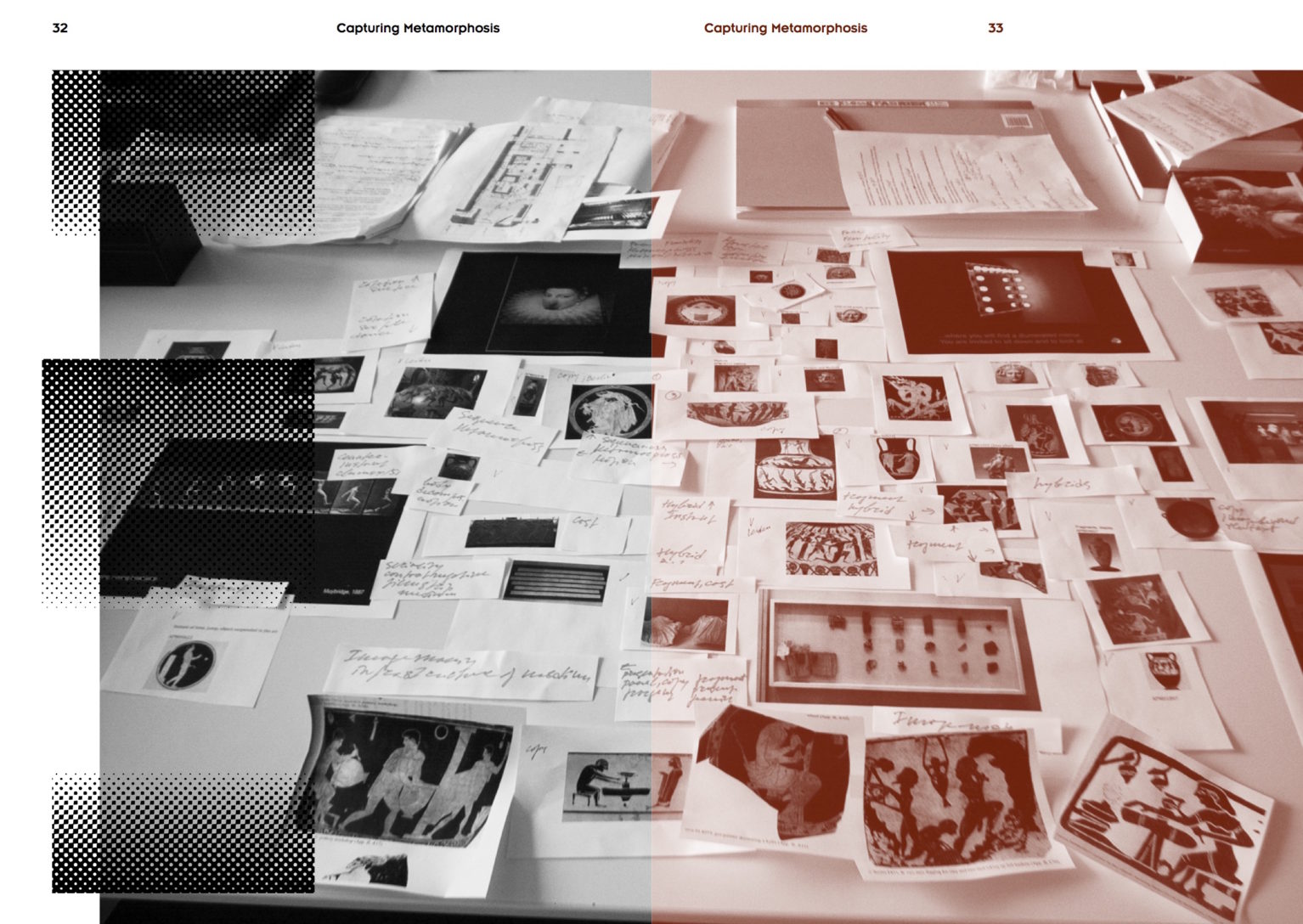

Capturing Metamorphosis takes a double perspective: not only does it explore metamorphosis as an event, but also as an aspect of images and as an artistic strategy. Three interrelated themes – the visual representations of metamorphosis; images of motion and the moving image; and image-making as a transformative practice – provide a framework for creating an unusual (and almost impossible) juxtaposition between ancient and contemporary art and media.

James Beckett, Rob Johannesma, Lawrence Malstaf, Barbara Philipp and Rebecca Sakoun have created new works, taking the concept of metamorphosis and the collection of ancient Greek art held by the Allard Pierson Museum as their point of departure. The visual motif of metamorphosis does not merely represent fantastic transformations into animals or plants, but also, more precisely, the transformability and plasticity of bodies, their ability to (re-)invent themselves constantly, and to be (re-)invented. This motif also tells another story – the story of image-making as an activity that involves the changing of forms. It is both a visual event that affects the appearance of bodies and an imaginary, fictional one; to make an image means to create a fiction. Capturing Metamorphosis takes the motif of fantastic transformations in order to read through it, to read it against its grain, to read another story – the story of how images are made, that of the medium and media. Ancient artists actually invented metamorphosis by representing it in stories and images. Present-day media claim that they can capture the minimal grains of time in which change happens. But perhaps by doing so, they invent an entirely new image, one that has never been seen before. Thus, in a sense, they too invent the instant of metamorphosis.

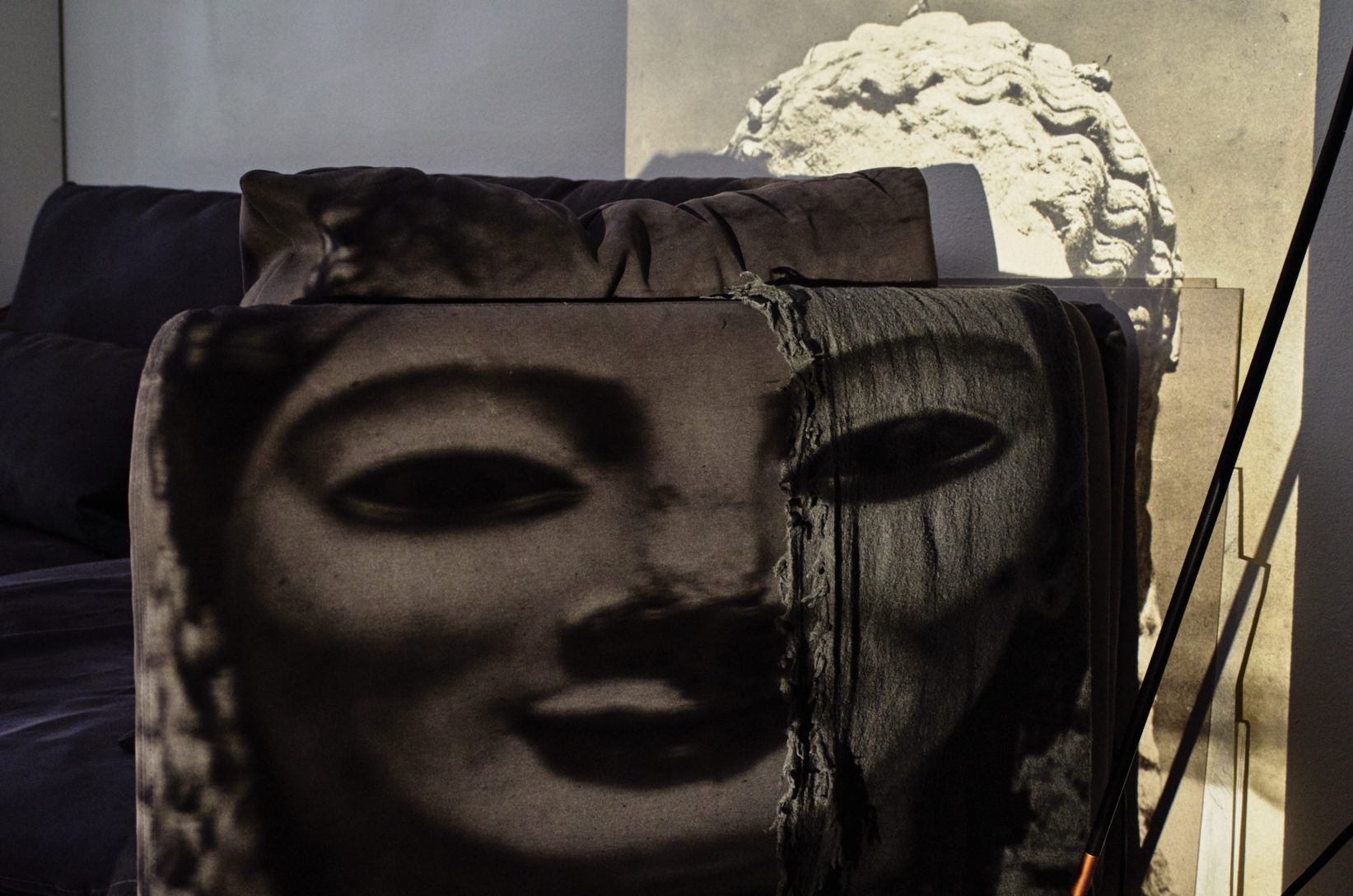

Hypothesis of a Lost Fragment, exhibition at YGREC, École nationale supérieure d’arts de Paris Cergy, 2015

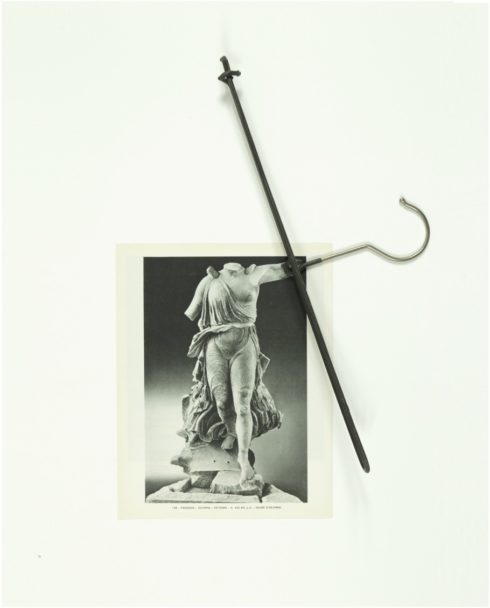

Archives, collections, catalogues, maps, technical gestures and scientific vocabularies, capture a variety of artifacts, images and territories. Archaeology is driven by the desire for understanding the past through recovering its fragments, and resurfaces in contemporary art practices as a trope and an open model. Artists mimic and displace its operations to question the construction of historical narratives and the complex positioning of objects in time — their fundamental anachronicity. The inherent freedom, or openness of the artistic operation (historically speaking a relatively recent feature) opens a space for an anarchic gesture. Where ‘anarchic’ is not understood in a directly political sense, but as recovering and recapturing the inherent undecidability of archives and media. This also includes in a broad sense, devices of capture whose infrastructures constitute the background, which both invents and guarantees the truth status of objects. Such infrastructures are carefully negotiated fictions, the result of highly mediated procedures of interpretation. The architecture of the archive, the frame, the camera, or the musical score articulate visibilities or sound events, while themselves remaining invisible or overlooked. Anarcheology, then, engages with the multiple meaningfulness of infrastructures by transforming them into visual objects. This not only opens a possibility of unfixing historical objects with regards to their assigned identities, with regards to narratives of origins, but more importantly of making visible the anarchic aspect of apparatuses themselves.

On which fields of knowledge are you focused?

Art theory, visual culture and photography.

What is the object of your research?

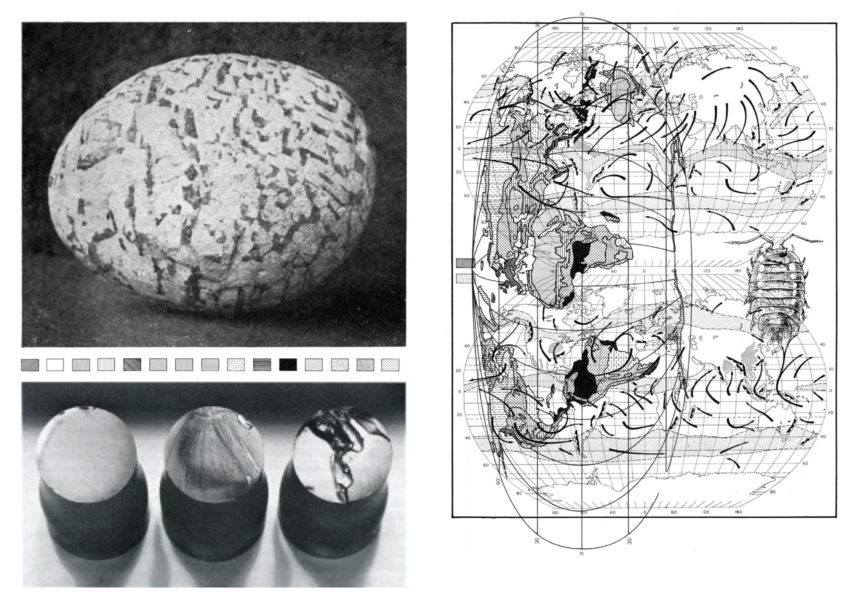

I am writing a book Anarchic Infrastructures: Recasting the Archive, Displacing Chronologies which addresses a constellation of contemporary art practices in a three-fold perspective. I look at the ways artists as Batia Suter, Rob Johannesma, Alexandra Navratil, Sascha Pohle, Maartje Fliervoet and others re-enact and use the atlas approach, reflect on histories of media and obsolescence, and use archeology and its operations as a broader conceptual figure. In this constellation central role is played by photography as the medium of archives, documents, also in the way it is used as a found material. Accumulations of photographic images into archives have a memory function, but in many cases the images have lost the link to the objects they represent and become photographic ruins. The photographic object becomes a second-level surface, and artists use different approaches to re-animation of image collections and archival images in their practises. Such approaches don’t fall into the category of archival art in the sense that they don’t attempt to fix the omissions of history, but create micro-histories of media and modes of looking. This reflection on the role of photographic images as constellations and as series as allowing the visibility of a motif to emerge resonate closely with the Mnemosyne Atlas, but they reveal in a different way the potentials of atlases. Each chapter captures a tendency, or a distinct interest demonstrated by artists in their practices – the return to analog film and photography, the archival, and the interest in writing histories through and with images.

The research for Anarchic Infrastructures provided the framework for an exhibition and symposium at PuntWG, Amsterdam including works by Maartje Fliervoet, Noa Giniger, Yoeri Guépin, Rob Johannesma, Gabriel Jones, Suska Mackert, Tao G. Vrhovec Sambolec among others. In addition to being a representation of a cultural order, museum collections, libraries, archives, are spaces of crisis or of infinite possibilities of juxtaposition and reinterpretation. Many present-day art practices are sensitive to both the contemporary dematerialization of the object, and to the materiality of the archive. They appropriate the scientific claim of research to alienate it from itself, so as to bring to visibility the apparatuses, structures and operations that claim to produce the identity of historical fragments and objects. The participating artists set in motion variety of archival visual material and found images to create visual constellations, which displace images from their status as an evidence, or a masterpiece, and deprive them from their individual visibility to create anarchic lines of seeing. The symposium included a lecture and four afternoons of artist talks.

In addition to that, I would like to mention two lectures on artists whose works I am discussing in my book

The Universe is Radiant: Reimagining Mnemosyne, De Waag, Amsterdam 2018

Departing from Roger Caillois’ proposition for a ‘diagonal science’, the lecture discusses art practices, which enact and revisit forms of visual knowledge as inaugurated by Aby Warburg’s last project the Atlas Mnemosyne. I explored Batia Suter’s Parallel Encyclopedia I and II (2008, 2016) and its promise of another type, parallel, or diagonal knowledge through the open resonance with the structures of devices as the encyclopedia, the atlas, and the map. Parallel Encyclopedia works with the weight of the photographic image as a document, found image, fragment, and its relationship to memory as a cumulative and entropic process.

After-Memory: Floating Image Histories, Eye Filmmuseum Amsterdam, 2018

In many of her films and installations Alexandra Navratil examines critically the histories of the material media of film and photography. By extension, she contemplates the plasticity and the constant redefinition of the concepts of document, evidence and memory. Her work involves extensive archival research and tells stories, both poetically and reflexively, of histories of images and their media. Her research process involves an intimate mode of witnessing, an emotional, empathic response to images and taking a position that both carefully considers their status as documents and re-assembles them on a more abstract plane. Navratil’s work and research pose the big questions of memory and of histories of images. How do we understand memory on an implicit level? What models of memory do we have – accumulation of records into a storage; a dynamic inscription surface that reforms itself latently?

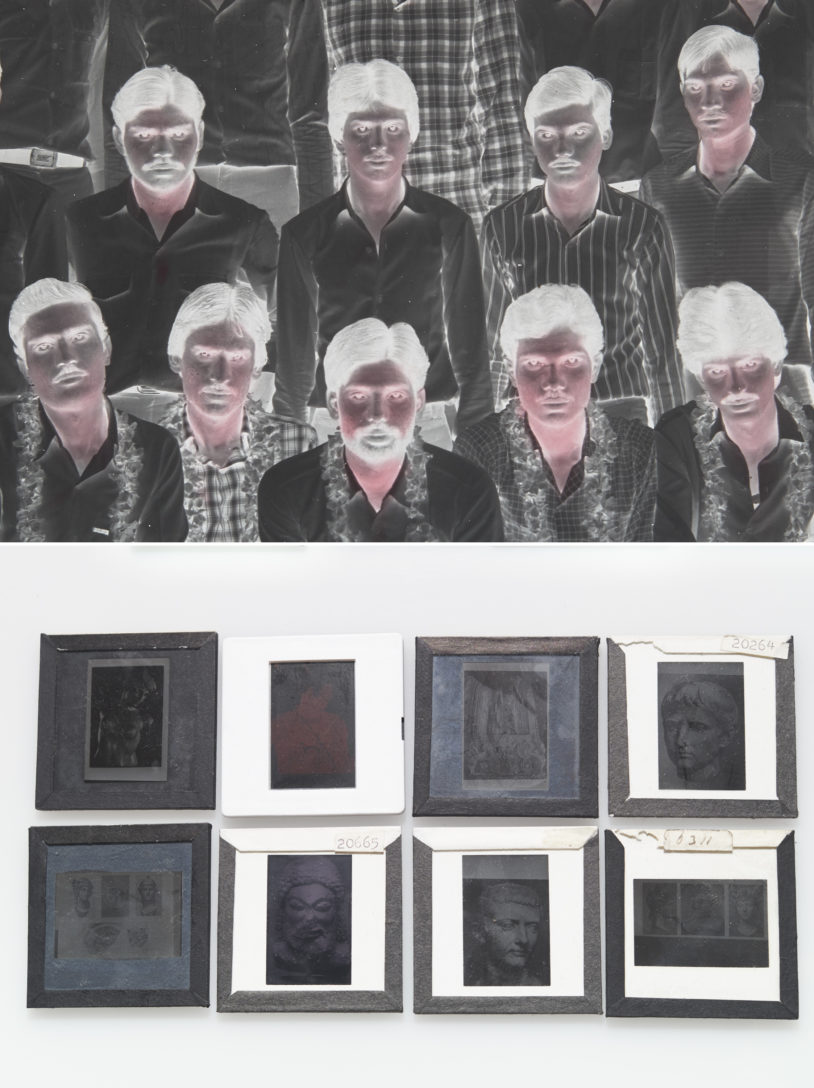

Next to this I am developing a project with photographer Johannes Schwartz – Portraits in Reverse. We work together and exchange ideas and visual approaches to reanimate two archival objects, each of us kept for a long time. Johannes has black and white negatives of studio group portraits dating from the 1930’s to the 1970’s in India. The negatives had no more use to the studios and he acquired them in the 90s. I kept some couple of hundreds of educational slides discarded by the Archaeology Department of the University of Amsterdam. For us these two collections have a big value beyond their original function and articulate different knowledge and stories than the ones, they were initially meant to tell. There are parallels, similarities and a certain companionship of the two groups.They are material fragments with a status of photographic ruins and deserve to be seen again as material and visual objects. We look at these images precisely as a group, as an image-multiplicity, an atlas of sorts, to reflect on the face, the portait and photography not only as a memory medium, but one of forgetting. Our object is in a sense an anti-archive, a group of images that have lost not only their documentary value, but also their order or organization. Working with such material we examine questions as how image accumulations that have lost their function as archives relate to oblivion, and possibly to different forms of collective memory.

Could you identify some constants in your work?

The passion for science, the creation of mythologies and the identification of personal symbols, the use of personal or others’ memory, the declination / adaptation of texts into images and vice versa …

I have always been fascinated by the manifold lives of images. The surface of images is always double, and the same counts for visual experience. Images transmit motifs and depict, but always reflect the (hi-)stories of their making and media. Photography as a medium is especially attuned to, and capable of creating and reflecting on this double surface. It captures, freezes the world and its visual texture into its perfect semblance and invites a particular kind of empathetic response. A specific motif that interests me is the way images can articulate and mark disappearances. From empathy to entropy, from the family photograph and the selfie, to conceptual photography and the way it thinks its own conditions, from surface and pattern, to the mask, the photographic archive, and the atlas as its animation; all these photographic gestures articulate forms of visual thinking and invite strange form of empathy with images that simultaneously draw and resist the gaze.

How did you find out about Aby Warburg’s work?

My interest in Aby Warburg began when I was writing my doctoral dissertation. I was researching the life and transformation of religious motifs and the way they can completely invert their meaning in contemporary artworks. Later, Warburg’s ideas continued to be important in my research, specifically the Mnemosyne Atlas as accessing memory processes through visual constellations and forms of organization, and also as an image in motion, as related to intimate knowledge of the ways images ‘carry’ emotions and bind with them. In my current project I am looking at the way artists use the atlas approach, as used by many artists, and the role of photography and its relationship both to memory and forgetting.

How would you define an Atlas?

Atlas can be defined in a variety of ways. Atlases can be tools of positivist knowledge by illustrating orders, structures and organizations. Warburg used the atlas as research approach that reveals visibilities and connections and collective memory processes or their crisis, and not as a fixed illustration of an underlying order. In his key essay What is an Author? Foucault remarks that with psychoanalysis Freud established an “endless possibility of discourse.” Similarly, Warburg’s Atlas opens a particular way of historicizing through images, which can generate endless variations. For me the atlas is a dynamic surface that has capacity to expand and put into play variety of principles, and approaches that consider the subject matter and the medium of images. It also allows for unconscious projections and it is a tool for image analysis and for making connections and not only revealing them. In this sense it is at the heart of the creative process. It allows for the simultaneous presence of fragments and does not to fix them in a linear narrative interpretation. The figure of Atlas, the titan that carries the world, suggests a representation of the world, but Warburg’s Atlas and the approaches it inspires, is in fact also a way of making worlds.

Atlas as a conceptual, formal and mnemonic device; do you use it in your work?

In my book Anarchic Infrastructures I am looking at the way artists use the atlas approach.

A particular aspect of these atlases, which interests me is the way iconic resonances and resemblances allow establishing connections between images, but also allow for endless analogies between images and can result in a condition in which everything is potentially connected. This specific form of mimicry and erasure of distinctions can be understood as a double process – of searching for and establishing new networks of meaning and simultaneously as a process of loss of organization and meaning through oversaturation with possible connections, an entropic process. This is an aspect of image accumulations, perhaps mostly photographic images, in their role as documentation and reproduction of artworks and other images. For me the atlas is also a research tool, but a very open one. It is a puzzle without a final frame, which sets thinking processes in motion and allows images to be used as tools to look at other images and reveal histories. The atlas is also an anarchic space where meanings emerge from constellations of fragments. What is particularly interesting is its capacity to expand., it is a network, which can grow and complicate itself endlessly.

Recently I became very interested in fragments or ideas, concepts, images, research directions that are excluded from a finished chapter or book, simply because one has to make choices and keep a particular focus. But I realized that these exclusions, what remains “outside the text” have a very big potential and have a special status of unfinished thoughts and personal fascinations. Putting together fragments from literature, theory, philosophy is not random, but is formed by my interests and determined by me as a person. In this sense, this approach creates a form of a self-portrait, and it allows to consider the personal as intellectual.

In another project of mine, it is a series of perfomative lectures, I use some principles that can be associated with the atlas approach. I reenact my working table and I create a constellation including all the abandoned ideas and excluded text fragments. It becomes a semi-structured journey through reading aloud quotes and text fragments, which I connect through association principles that are not always transparent and hold a trace of particular connection between concepts I wanted to consider, but they were never developed. The atlas approach allows for this association and conceptual travels.

I use the atlas approach as a curatorial principle. It allows to make connections across time and media and to look at metamorphoses of motifs. It is also a metamorphic approach that allows for transformation and new articulations, to depart from the visual and not factual, and for different kind of knowledge. I have fascination for maps and territories of conceptual and visual spaces because they allow one to perceive images, objects and ideas, not as static but as having migrating identities. In teaching art students I invite them to engage with their own image archives and experience the process of creating their own atlases, create visual constellations and look to research through images.

Do you know about the existence of Mnemotechnics?

Yes.

Which mnemonic system guides the organization of your material?

Before I start writing, I make maps, conceptual ones. The distribution and visibility of questions and ideas in the space of a page or a table, allows me to see connections and directions for further research. I am also very interested in the potential of chance encounters with material and the way this can sometimes have very big influence on my work.

Are there visual and emotional formulas (pathosformeln) in your project?

I am very interested in our empathy response to images and the way they bind with our emotional life. But this is a project I would like to develop in the future.

In your work, do you identify formal or conceptual recurrences such as repetitions and disruption, distance and proximity, identity and migration, conflict and colonization?

In Anarchic Infrastructures I am looking at the way artists mobilize processes and techniques as repetition, disruption, iconic and formal resonances and contrasts, but also subtraction and reduction in order to reflect on the histories of the media of film and photography, and to create critical visibilities, which are not often allowed by archival orders. I am very interested in also analogy and mimicry as a way to erase difference and identity, and to invitinge to critical ways of looking. In a way some of these features also structure my own working process.

In your work, what is the balance between image and text?

Images have specific weight and effects beyond art historical questions of period and style. I am very interested in their emotional resonance, and their “valence” but also in their mediality. Images can be also a tool to see and animate other material. In Portraits in Reverse we are animating archive object by using images as “lens” to look at other images.

Thinking about Warburg’s ‘good neighborhood rule’, what are the books that underpin your project?

Giorgio Agamben, Potentialities, translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999)

Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus, translated by David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009)

Barbara Baert, Wind. On the Origin of Emotion, translated by Irene Schaudies (KU Leuven, 2012)

Hans Belting, Anthropology of Images: Picture, Medium, Body, translated by Thomas Dunlap(Princeton University Press, 2011)

Benjamin Buchloh, “Gerhard Richter’s Atlas: The Anomic Archive” October 88: Spring 1999

Roger Caillois, “A New Plea for Diagonal Science” In: The Edge of Surrealism, translated by Claudine Frank and Camille Naish (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003)

Roger Caillois, “Mimicry and the Legendary Psychastenia” October 31: Winter 1984

Georges Didi-Huberman, Atlas or How to Carry the World on One’s Back,exhibition catalogue (Madrid: Museo Reina Sofia, 2012)

Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images, translated by John Goodman (State College: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005)

Siegfried Kracauer, “Photography” Critical Inquiry, 1993:19 (orig. 1927)

Philippe-Alain Michaud, Aby Warburg and the Image in Motion, translated by Sophie Hawkes (New York: Zone Books, 2004)

Raul Ruiz, Poetics of Cinema, translated by Brian Holmes (Paris: DisVoir, 2005)

Reiner Schürmann, Heidegger on Beling and Acting: From Principles to Anarchy, translated by Christine-Marie Gros (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

W.G.Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, translated by Michael Hulse (London: Vintage Books, 2002)

Edouard Leve, Autoportrait, translated by Lorin Stein (London: Dalkey Archive Press, 2012)

Alena Alexandrova is a cultural theorist and an independent curator based in Amsterdam. She lectures at the Fine Arts and Photography departments, Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam. She holds a PhD from the University of Amsterdam. Currently she is writing a book Anarchic Infrastructures. She is the author of Breaking Resemblance (Fordham University Press, 2017). She has published internationally in the fields of aesthetics, performance and visual studies, and regularly contributes to art publications and catalogues. She curated several exhibitions around the conceptual figure of anarcheology in the work of contemporary artists. Previously she taught at the Master of Fine Arts, Faculty of Fine Art, Music and Design, University of Bergen, Norway and the Dutch Art Institute, Arnhem. She was a visiting researcher at the Humanities Center, Johns Hopkins University, Cité des Arts, Paris, and a guest lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts in Nuremberg.