Federico Clavarino, artist

Medusa (working title)

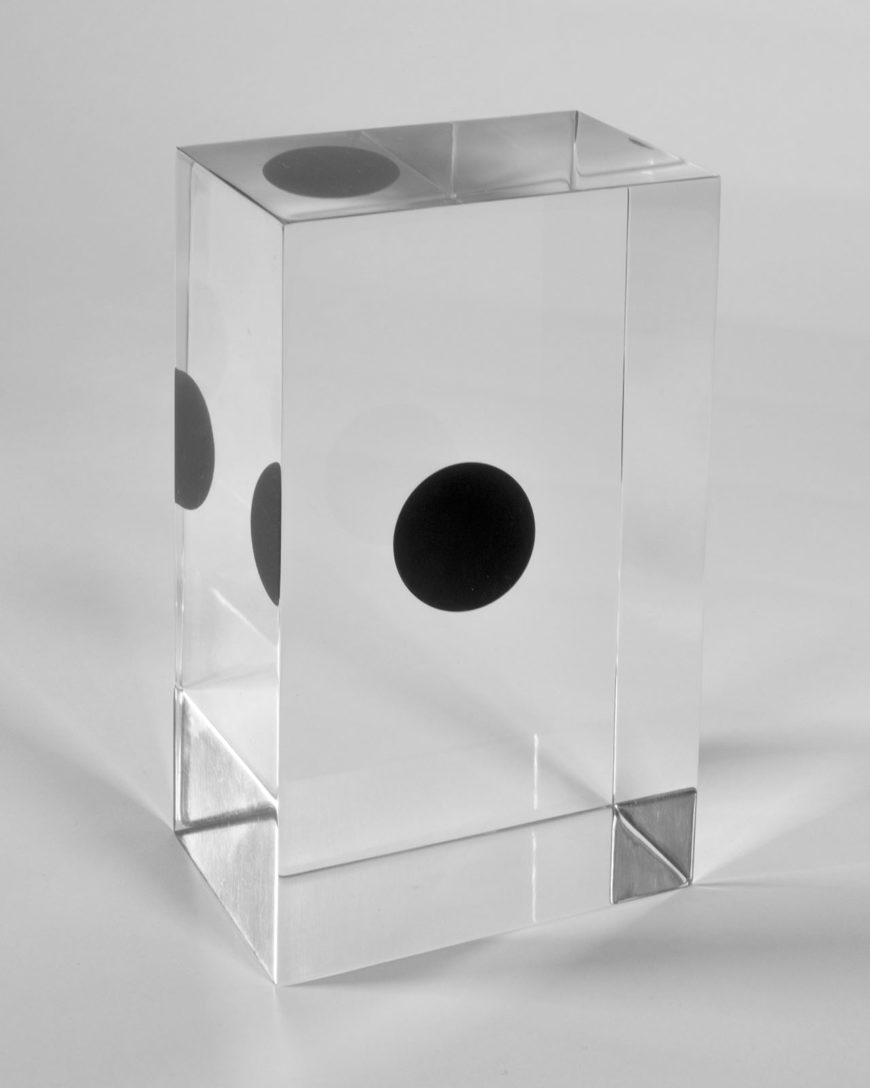

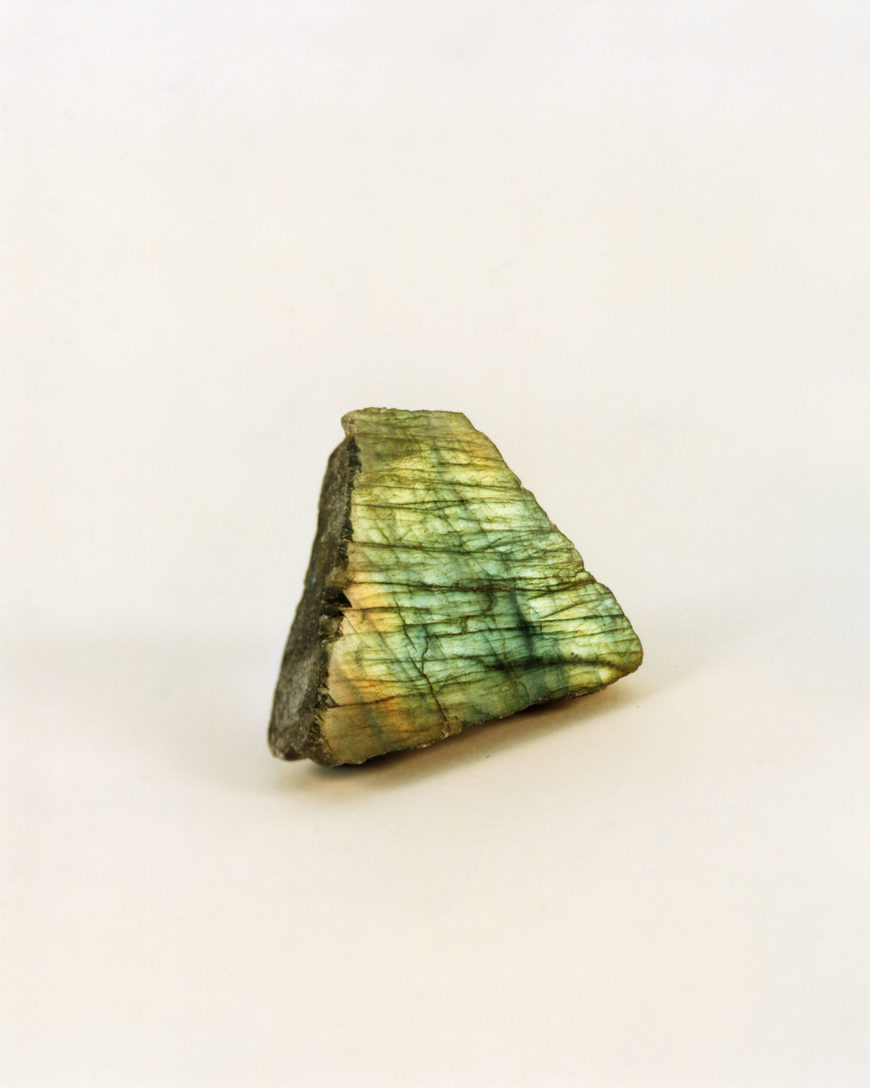

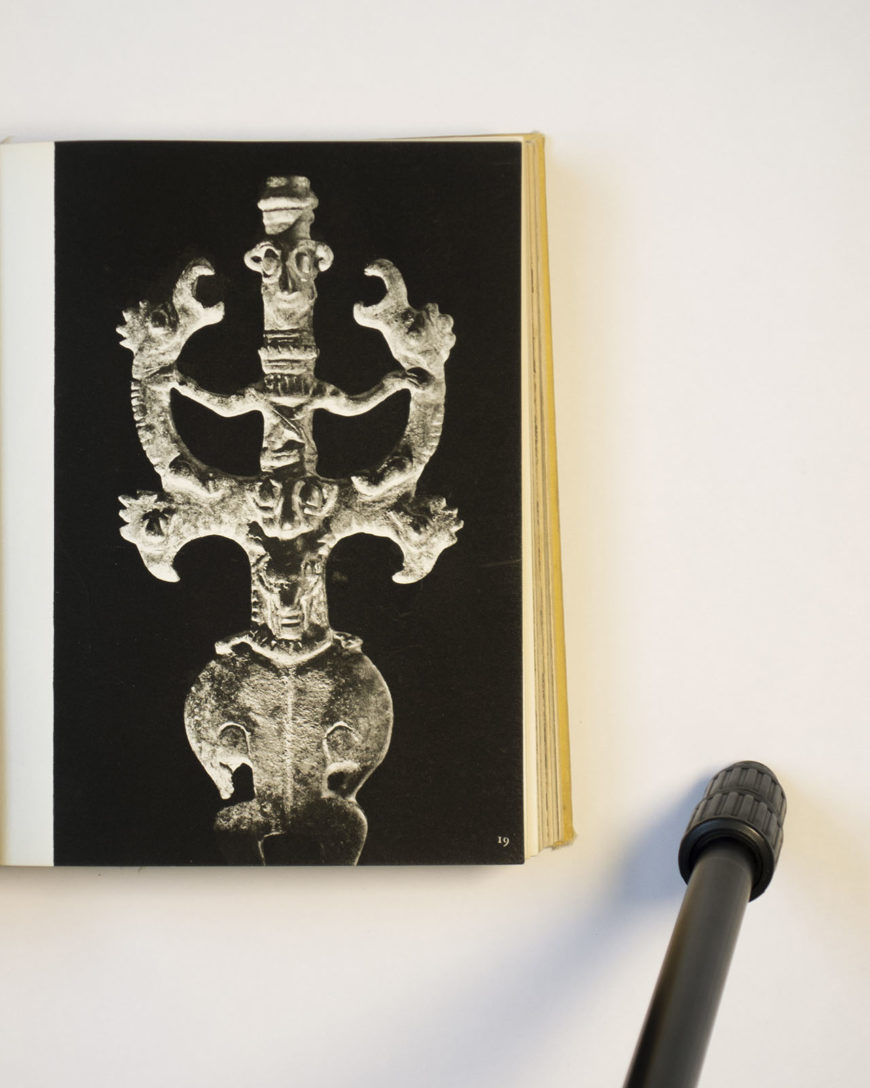

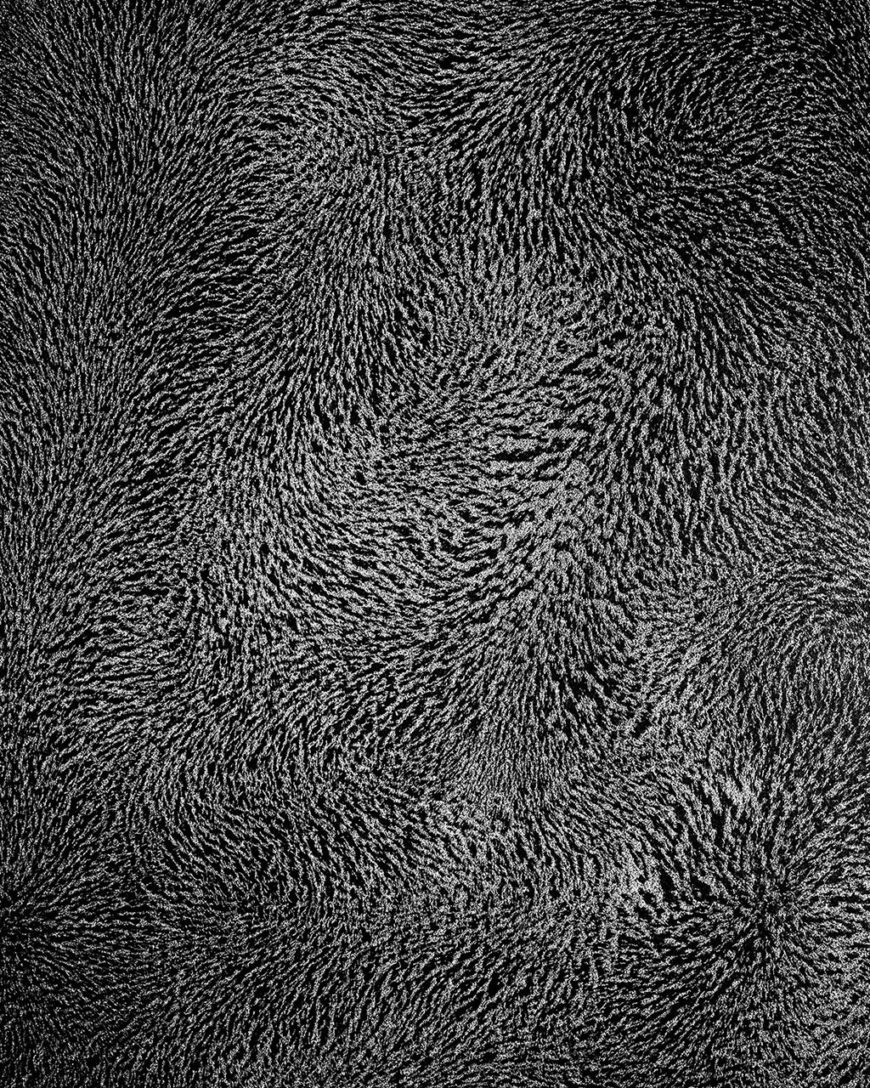

This is an ongoing research project, and one that just started, hence its rather chaotic structure. Broadly speaking, it is looking at the gesture of photography as embodied vision. It is about photography as an entanglement of subjects, objects and apparatuses as mutually defining entities. Its core is the specific subject-object gap opened by the gesture of machine-aided observation. It is about mechanisms of recognition and mis-recognition inaugurated by the gesture of photographic vision, and the photographic observation of gestures. It goes both ways, as I am constantly jumping from looking at photography and looking through photography. My guide is the Master of Animals, a Near-Eastern Iron Age motif depicting a human-like figure holding two snakes at arm’s length. The MoA emerges between me and myself, between me and my neighbours. It is the wound and the stitches, it is the screen which appears at the intersection of the eye and the gaze, the split that marks the subject. It is also the cut that momentarily resolves the indetermination within phenomena, thus enabling vision. My proposal is that this is a primordial camera. My practice is unfolding along different lines, by trying out various strategies, all of them involving the setting up of some kind of experimental apparatus. The thinking evolves by jumping between them, as if it were some kind of 3D atlas or diagram.

On which fields of knowledge are you focused?

Photography, history, literature, philosophy.

What is the object of your research?

Vision and Gesture.

Could you identify some constants in your work?

History as a site of haunting; Gesture as a place of inter-subjective recognition; The fragment as a method; The fabrication and perception of space; The entanglement of vision and desire (this is relatively new).

How did you find out about Aby Warburg’s work? What interests you the most?

My first encounters with Warburg was in a brief essay by Roberto Calasso (La follia che viene dalle ninfe, Adelphi 2005) and in the 2010 exhibition ATLAS, curated by Georges Didi-Huberman at Reina Sofia in Madrid. I then became acquainted with Didi-Huberman’s extensive research on Warburg and read some of his books and articles, and started exploring the Atlas on engramma.it. My interest for Warburg was aroused by the fact that we share a method. I have always thought like that, by mapping out images on surfaces and jumping around, following unexpected currents and generating paths and nodes. We also share an obsession for ghosts, maybe some kind of underlying melancholy, or just the strong sensation that history, to use Benjamin’s words, is not a “sequence of events like the beads on a rosary”. And then there’s gesture, that particular bodily condensation of psychic and affective energy.

How would you define an Atlas?

An Atlas is something of an assemblage. It differs from a map in that it is based on difference instead of equivalence, and in that its surface isn’t produced by one single dominating and unifying bird’s eye point of view. The atlas obeys the logic of the fragment, it is made of ruptures and sudden shifts, and it acknowledges and activates gaps. In fact, it feeds on gaps and interruptions, because it is there that knowledge is produced. An Atlas requires a very active viewer/reader/user, and its reading might change every time.

Atlas as a conceptual, formal and mnemonic device; do you use it in your work?

I use atlases in three ways: as a way of studying/researching and laying out references, as a way of sorting out my own production, and finally as a way of showing my work (although this might undergo different translations owing to changing media and contexts).

Do you know about the existence of Mnemotechnics?

Yes, I do.

Which mnemonic system guides the organization of your material?

I start out with underlining in books, taking notes, and making images, then I use different methods of sifting through what I found (involving little boxes with prints and cards, for example), and I finally use walls with post-it notes and small prints to map out my thoughts. I have a terrible memory, except for places. I forget words, stories and faces, but I always remember places, and often also images (still images, I have a hard time with moving images). So I use location and pictorial fragments to remember and think. This often requires some translation, and that is how much of the work is produced.

Are there visual and emotional formulas (pathosformeln) in your project?

Yes, I would dare say there are. The Master of Animals could be the most straightforward example, as it is its machinic incarnations I am after. There is also one part of the project in which I am working with someone who is modelling for me, and we are using a repertoire of recurring gestures I have observed in paintings, photographs and everyday life, which she then reinterprets from her own culture (she is Chinese) and subjectivity. As we know, it is in that kind of difference that formulas are reactivated, and their affective potential is summoned.

In your work, do you identify formal or conceptual recurrences such as repetitions and disruption, distance and proximity, identity and migration, conflict and colonization?

Yes, all the time. Both in previous works and this one. It would be difficult to address such big themes here though. We might want to break this question down into some of its elements in a future conversation. There is, though, a kind of underlying polar thinking in the question (proximity/distance, repetition/disruption, identity/difference) that I find worth looking at right now. The idea of thing flipping into their opposites is a fascinating one, that is at work in Warburg’s Atlas, and in so many other works that are relevant to my interests (I am thinking of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams now). The idea of polarity, of incommensurability, of dialectical tension, of splitting, of what Zizek calls “parallax gap” and Barad calles “agential cut”, lies at the heart of my research. But it’s still rather messy, a series of hunches.

In your work, what is the balance between image and text?

It is changing. My first works were devoid of text, then it came creeping in. I guess the balance I am interested in is in having the text doing what images cannot do, and the other way around, although there are so many overlaps and it’s interesting to play around with them too. It is interesting to consider a fragment of text as something that could work “as an image”, and the other way around. Now I am thinking of giving text a different kind of agency though. I am toying with the idea of working with extremely condensed images, and extremely dense text, to play with a huge amount of information, impossible to cope within the context of an exhibition (which is what I have in mind). I am also thinking that the text could be performed, and change every time.

Thinking about Warburg’s ‘good neighborhood rule’, what are the books that underpin your project?

Rosalind Krauss – The Optical Unconscious (MIT Press, 1994)

Victor Burgin – The Camera: Essence and Apparatus (MACK, 2018)

Lorenz Stoer – Geometria et Perspectiva (1567)

Vilem Flusser – Gestures (University of Minnesota Press, 2014)

Georges Didi-Huberman – The Surviving Image (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017)

Giorgio Agamben – L’aperto (Bollati Boringhieri, 2002)

Karen Barad – Meeting the Universe Halfway (Duke, 2007)

Michel Serres – Eyes (Bloomsbury, 2015)

George Bataille – Storia dell’occhio (SE, 2008)

Roger Caillois – The Edge of Surrealism (Duke, 2003)

Roberto Calasso, La follia che viene dalle ninfe, (Adelphi 2005)

Federico Clavarino is a photographer and teacher based in London. He studied creative writing at Alessandro Baricco’s Scuola Holden in Turin and documentary photography at Fosi Vegue’s BlankPaper Escuela in Madrid. He is currently pursuing a Master of Research degree at the Royal College of Art in London. Clavarino’s works revolve around issues of power, history and representation. He has published six books so far: Ukraina Pasport (Fiesta Ediciones, 2011), Italia o Italia (Akina, 2014), The Castle (Dalpine, 2016), La Vertigine (Witty Kiwi, 2017), Hereafter (Skinnerboox, 2019) and Alvalade (XYZ Books, 2019). His works have been exhibited internationally, in the official programme of festivals (PhotoEspaña, Les Recontres d’Arles, Fotofestiwal Łódź) in galleries (Viasaterna, Temple, Espace JB) and in museums (Caixa Forum, MACRO). He taught at BlankPaper Escuela from 2012 to 2017 and currently lectures and gives workshops internationally, collaborating with museums (MACRO, CCCB, Museo San Telmo), schools (ISSP, D.O.O.R.,Officine Fotografiche) and universities (Leeds, Roehampton, South Wales, Navarra).