Guido Guidi, photographer

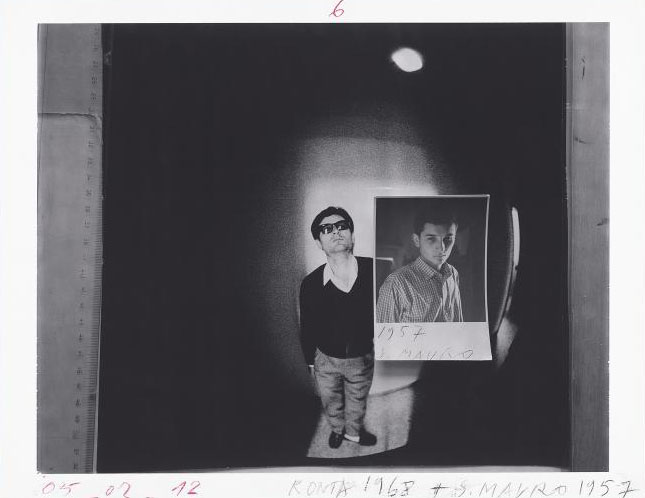

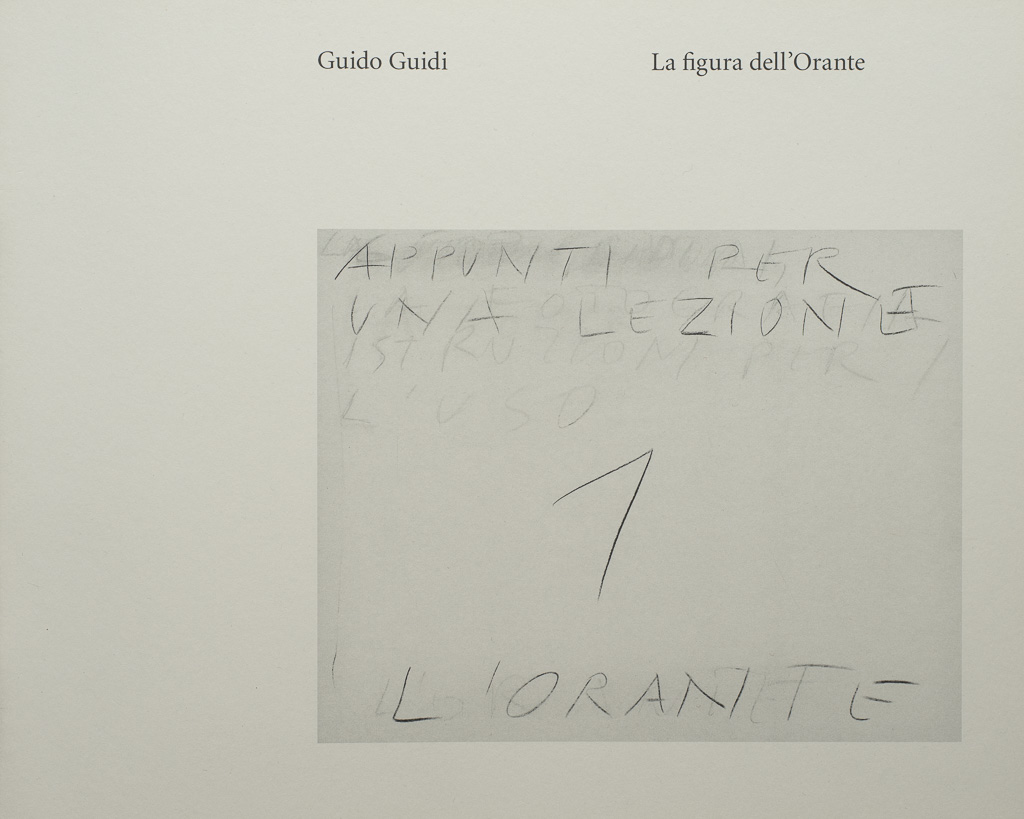

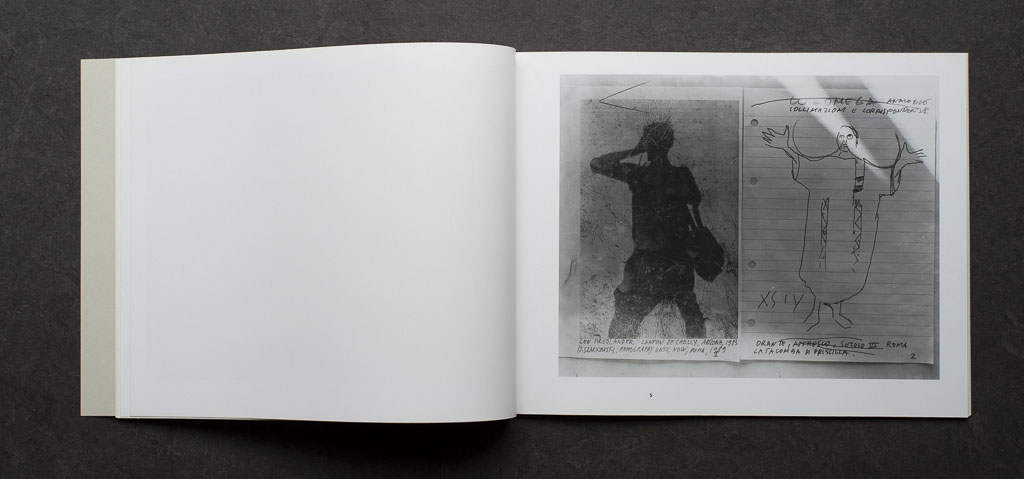

La figura dell’Orante. Appunti per una lezione, vol.1, Edizione del Bradipo, 2012

The following text is a free transcription of telephone conversations between Guido Guidi and Benedetta Cestelli Guidi

I am interested in how things look, not in what they are – I am definitely not a philosopher or an Indian guru! I explore different vantage points in accordance with the temporal nature of observation. Movement and time are my concerns. I studied Borromini’s architecture during the University years (I was then preparing History of architecture with Bruno Zevi), I guess that’s when I became interested in the dynamism of architecture. I had a chance to reflect on the apparent contradiction between architecture and movement as I was carrying out a measured and photographic survey of the Church of Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori in Rome.

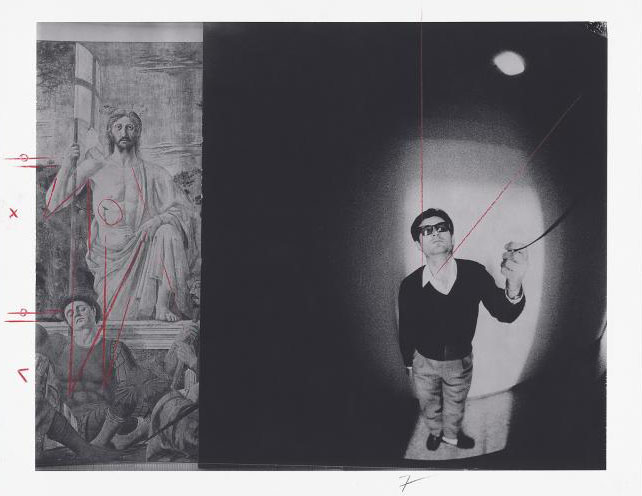

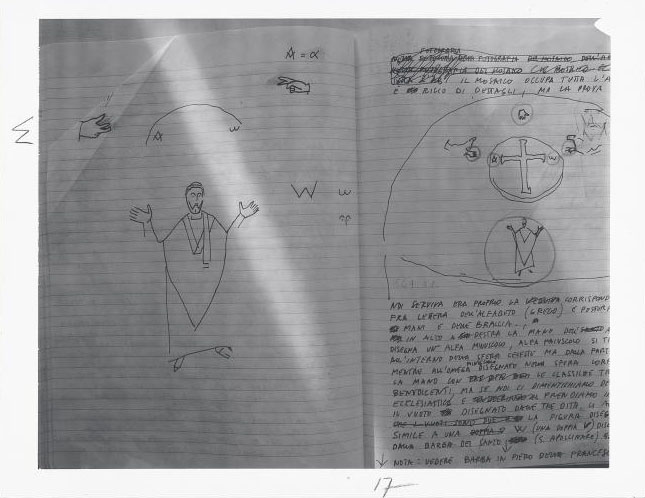

Later on I became interested in recurringshapes in visual art. My project La figura dell’Orante [The Figure of the Orans] revolves around a single shape – the Greek omega (ω) – that can be found in art works since late antiquity.

As I was investigating this persistency I realized that philological research and creative process, perhaps by chance, interplayed harmoniously. Working on the history of symbols and alphabets, studying paintings and artworks, and taking photographs at the same time, I found some kind of productive analogy between the archaic shape of the Omega and the idea of the optical cone as found in Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise, De Pictura (1435).

My interest in early Renaissance art theory, mainly in Fourteenth century writings, brought me since an early age to read extensively XX century art history and criticism. I read books written by Italian art and architecture historians (Lionello Venturi, Bruno Zevi, Giulio Carlo Argan, Nello Ponente) and by foreigner scholars (Ernst Gombrich, Andre Chastel, Sigfried Giedon). Among the latter I found extremely inspiring Erwin Panofsky essay on perspective, which he interpreted as a symbolic form. Lately I read and enjoyed Georges Didi- Huberman essays although my favorite book is Daniel Arasse Il dettaglio. La pittura vista da vicino.

I have many interests, undoubtedly photography as well as painting and drawing, architecture, music and literature. At a very young age I became fascinated by astronomy: my book Lunario spreads from there.

Photography has two components that I find crucial: the camera’s own language and the possibility to narrate what can’t be told otherwise. Surrealism aesthetic premises, with its strong anti traditional stand, appear to me to be fundamentals for photography; as, for instance, the process of loose association of forms/images on a surface.

In his first object trouvé Marcel Duchamp shifts on a performative level the strict photographic associative quality, the erasure of functional context, the inversion of meaning.

Could you identify some constants in your work?

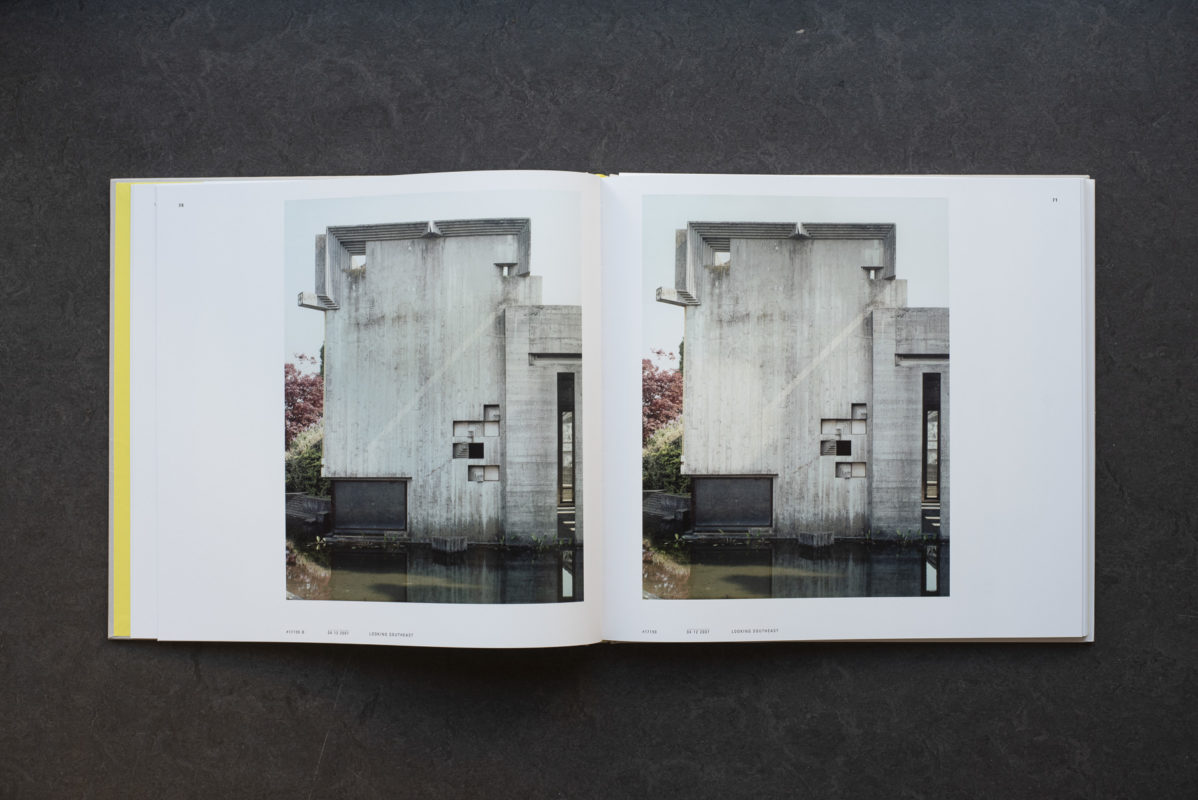

Persistence. I work mainly on the flowing of time. Carlo Scarpa architecture can be understood as a reflection on time. This is a dearest topic in venetian culture since the Renaissance (the old maid in a Giorgione painting [La Vecchia] holds a scrap of paper with the sentence ‘Col tempo’), and Scarpa updates it choosing unstable, prone to erosion building materials: wood that will decay, iron that will erode and get rusty.

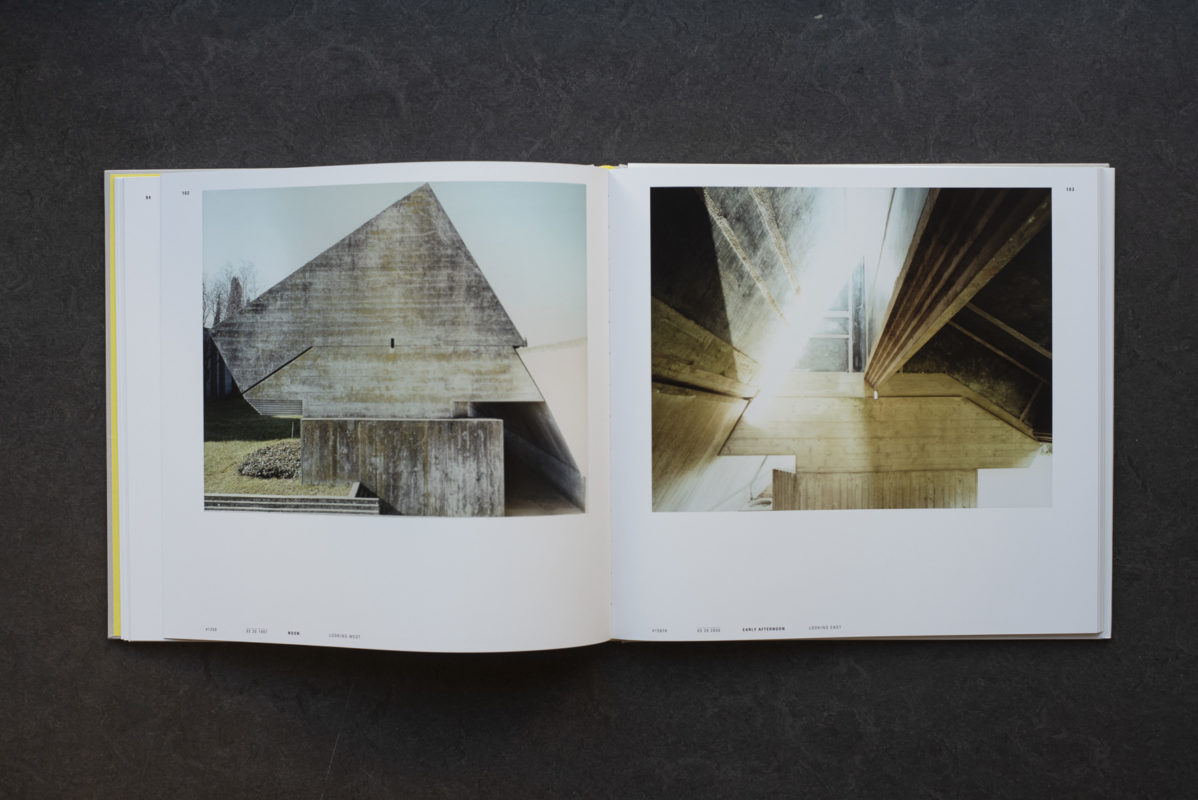

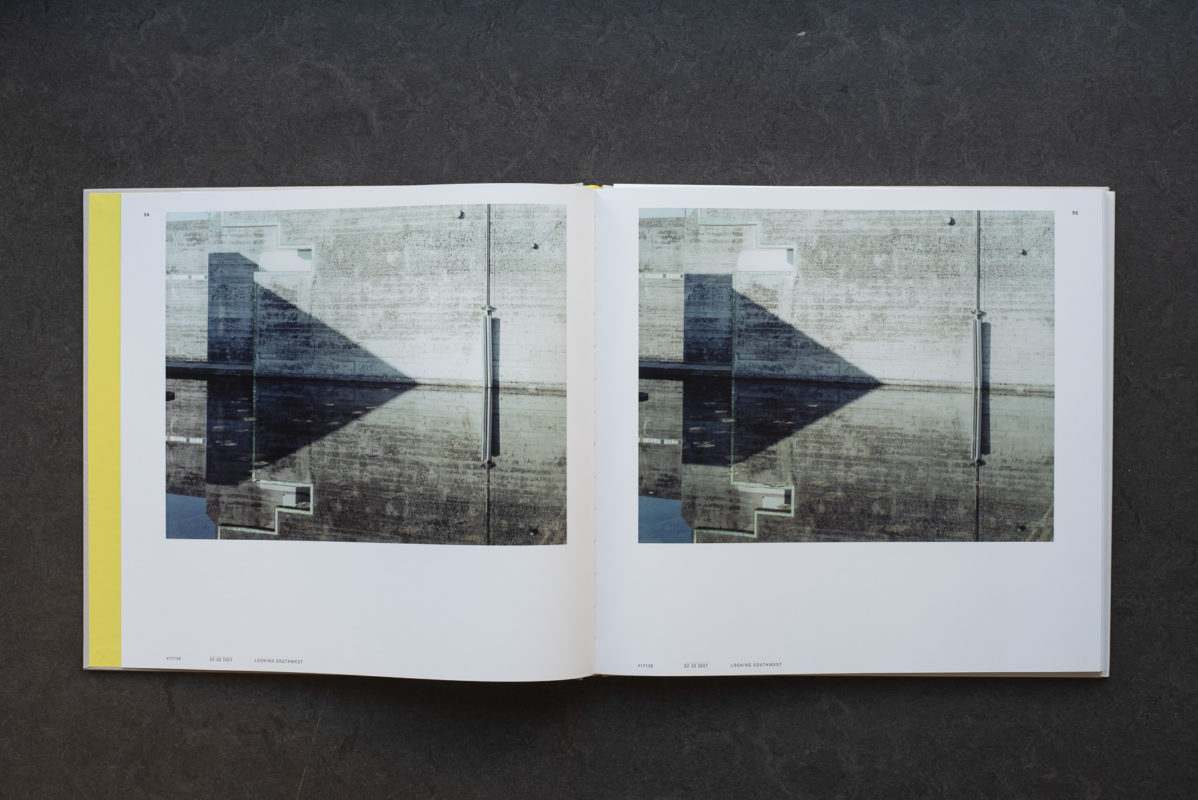

During my ten years long survey (1996 – 2006) on the Tomba Brion, build by Scarpa in 1970 – 1978, I watched the interplay between light and architecture and then put into images the gradual changes the monument underwent as a consequence of it. Whilst I was setting up the photographs I became aware of a recurrent shape, both in the architecture and in the way light stood out in the interior: a triangular shape, an arrow shaped form that would modify both surface and our optical perception of it. It was the very same shape that, in a cyclic process, would undergo changes during the passing day and seasons. In order to visually record this process, by which I was then amazed, it became necessary to choose one and only view point and stay still during the long passing day: from the chosen spot I shoot the ever changing shapes projected by sunlight on the architecture surfaces.

This way of working rests on two opposing elements, usually perceived as conflictual that I, on the contrary, believe to be complementary: stillness and variation.

Focusing on the arrow-shape I felt the need to track down Scarpa own’s reference points, and necessarily went back to Paul Klee compositions. Klee was highly valued by Scarpa and we, then young University students, were taught to consider him a ‘maestro’. The arrow shape is crucial to Klee as well, and he uses it persistently in more than one drawing and painting.

I am interested in the way things change due to the effect of light. Light activates minimal processes of alterations and produces unstable and ever changing relations; this variability concern and involve both form and content.

How did you find out about Aby Warburg’s work? What interest you the most?

I have known Warburg since my university years, although I have never read his essays. Carlo Scarpa acted as a mediator, at least as a start, and during the following years I have heard more and more about him. I have mainly been interested in his inclination to muddy the waters, re-set the art narrative and dismantle the system of evaluation of art works: the art canon is reversed, for instance, when a stamp is mounted next to a Giorgione painting (in a panel of the BilderAtlas Mnemosyne or in an essays). I find this subversion interesting.

How would you define an Atlas?

An Atlas is what is printed in primary school books; a geographical map of a continent or a nation placed next to images reproducing social and natural topics.

Atlas as a conceptual, formal and mnemonic device; do you use it in your work?

An Atlas could reproduce the whole hearth, would be a comprehensive tool. Therefore no I do not use it, but I am interested in it.

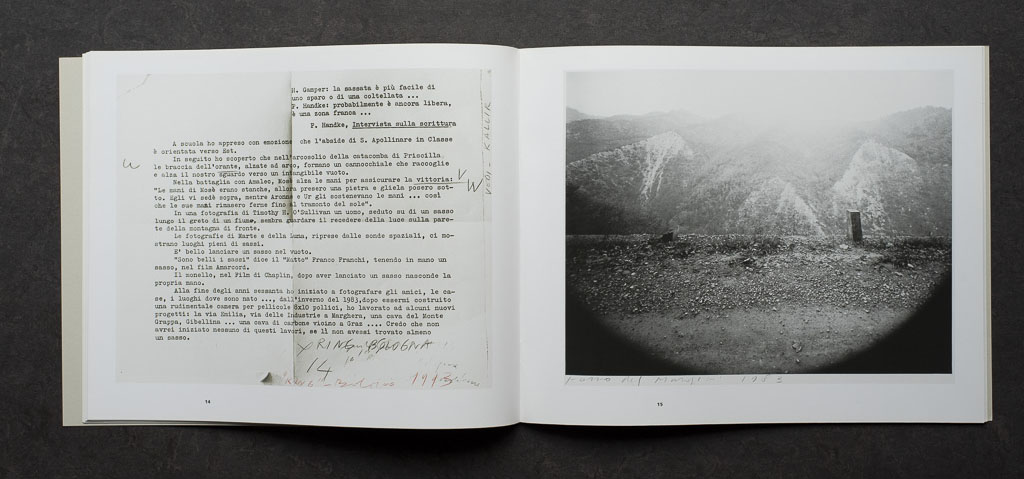

Although I published a book titled Rimini Atlas, focused on the inner region of Emilia, my work is not built on a strict typological organization of places or photographs.

I would like to make an Atlas of doors since a door hides what is beyond it, and is a space to start thinking. My own interest in doors was enhanced by Arasse interpretation of Fourtheen century Annunciation paintings: a door is always within the painting and works as a duplicate of the Virgin Mary: it would be an Atlante della Madonna. I approached the issue already in a sequence of photographs shoot in 1983 called Preganziol; I photographed the light entering in a room at different daytimes. The changing lights in a space deprived of its traditional holiness quotes Renaissance paintings in which an angel, not simple light enters from the window. Nowadays we don’t believe any longer in angels and what’s left is light.

Do you know about the existence of Mnemotechnics?

Yes, I have read about it in Arasse book Storie di pitture.

Which mnemonic system guides the organization of your material?

I am not methodical. Despite the apparent chaos, my archive seems to be ruled by a complex order which I wishfully think to have under control.

In your work, what is the balance between image and text?

Representation holds its beauty in uncertainty, is a space of suspension, mystery. ‘Painting’ is female whilst ‘word/verb’ are male.

Arasse maintains that paintings are true documents from which to gather informations, although he believes that visual language is potentially misleading when compared to verbal one which, on the contrary, tries to scrupulously define.

If for instance I paint an ircocervo – a fantasy creature – when I look at the painting it exist; similarly if I see a painted pipe I assume it is a pipe: I must recur to writing to state that they are not real but mere representation of existing/out of fantasy objects. Visual experience allows to enter space, but is a depiction not real space.

Thinking about Warburg’s ‘good neighborhood rule’, what are the books that underpin your project?

Anton Checov, I Racconti, Feltrinelli 2014

Italo Zannier, Storia e tecnica della fotografia, Hoepli 1985

Italo Zannier, La fotografia soprattutto, Mimesis edizioni 2019

Olivier Lugon, Lo stile documentario in fotografia. Da August Sander a Walker Evans 1920 – 1945, Electa 2008

Heinrich Schwarz, Arte e fotografia. Precursori e influenze, a cura di Paolo Costantini, Bollati Boringhieri 1992

Robert Adams, La bellezza in fotografia. Saggi in difesa dei valori tradizionali, a cura di Paolo Costantini, Bollati Boringhieri 2012

Eugen Herrigel, Lo zen e il tiro con l’arco, Adelphi 1987

John Szarkowski, Photography until now, Museum of Modern Art 1989

Jerry L. Thompson, A che serve la fotografia, Postmedia books 2013

Lewis Baltz, Scritti, a cura di A. Frongia, johan&levi editore, 2014

Susan Sontag, Sulla fotografia. Realtà e immagini nella nostra società, Einaudi 2004

James Joyce, Ulisse, Mondadori 1984

Carlo Emilio Gadda, La cognizione del dolore, Adelphi 2017

Daniel Arasse, Il dettaglio. La pittura vista da vicino, Il Saggiatore 2007

Daniel Arasse, Il soggetto nel quadro. Saggi d’iconografia analitica, ETS 2010

Bruno Zevi, Saper vedere l’architettura. Saggio sull’interpretazione spaziale dell’architettura, Einaudi 2009

Bruno Zevi, Storia dell’architettura moderna, Einaudi 2010

Siegfried Gideon, Spazio tempo architettura, Hoepli 1984

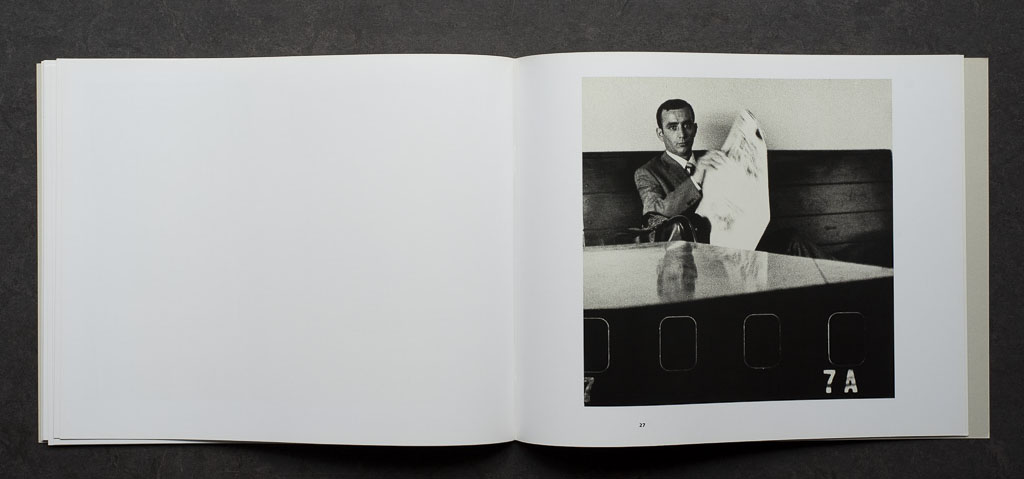

Michelangelo Antonioni, l’intera filmografia

Are There more topics of interest that we haven’t pinned down?

During the fascist time no one cared about urban context, the link between a single monument and the overall urban structure.

What is a city nowadays? I belong to those who identify a city with its historical center, and I am influenced by a specific cultural approach. According to Marco Venturi a city was once like a boiled egg, then became a fried egg and today is a scrambled egg. The historical town center is no longer an insulated monument but on the contrary a spatial continuum made out of new building and roads. Today a city is a sort of a Warburg like structure and context is the most relevant issue. The idea of preserving the overall urban context in its integrity without a hierarchy belongs to Warburg system of thought; if only a chimney is preserved, it will become the only surviving trace of a process (in this case a urbanistic one) that can’t be fully grasped unless we are able to link the chimney to its previous context.

Urban planning, as well as photography is made with our feet. Whilst walking one changes his/her perceptions of things and on the other hand I am being changed: I undergo a transformation by opening up a dialogue between myself and what I look at. To me movement is at the core of knowledge, and contemporary art is based on process, on doing: process is the central part of art.

Guido Guidi was born in Cesena, Italy, in 1941. He studied in Venice at the University Institute of Architecture (now IUAV), where he followed the courses of Bruno Zevi, Carlo Scarpa and Mario De Luigi, and at the Advanced Course in Industrial Design with Italo Zannier and Luigi Veronesi. He has worked as photographer at IUAV Department of City Planning since 1970, and has taught photography at Ravenna Academy of Fine Arts since 1989 and at IUAV – where he holds the Laboratory of Artistic Techniques and Expressions – since 2001. His work is currently under publication for MACK books.