Carla Rak, artist

Eyes as Oars. A Visual Journey to Mars, published by Danilo Montanari editore, 2018

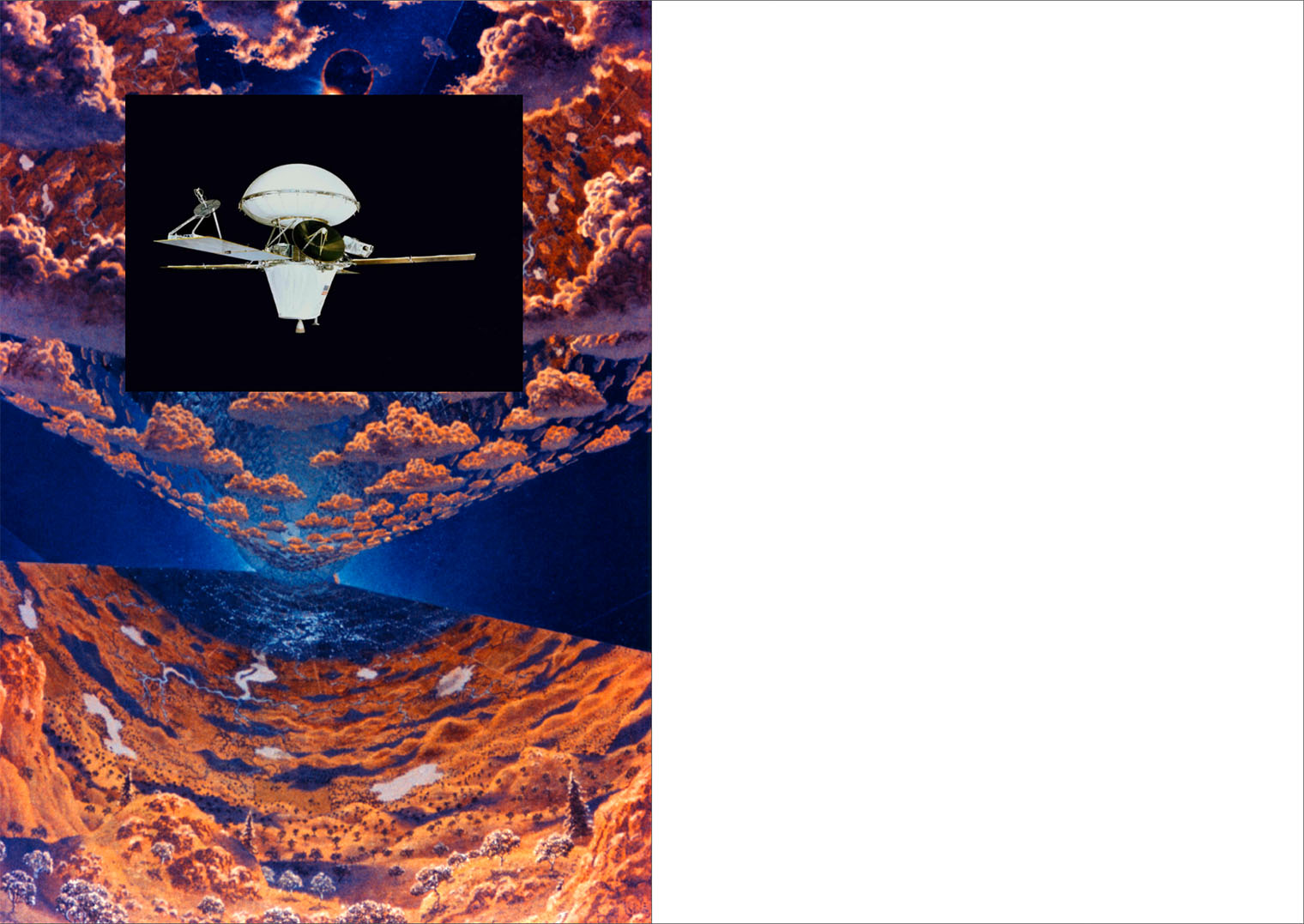

Since the advent of magic lanterns in 17th century, images have unfolded and revealed their powerful kinetic potential: without moving from his/her home the viewer can travel worldwide with dizzyingly acceleration and/or sudden stops. No one has ever been to Mars but today we can explore it with our own eyes thanks to NASA images, which allow us to experience that centuries old innovation: we explore with the sense of sight. NASA’s documentary photography together with diverse Public Domain authorized images taken in different time spans and from various sources, are the visual maps of an imaginary journey to Mars. The visual journey takes into account both accurate photographs used for the Red planet’s scientific observation, our shared popular image of it, our emotional perception of potential links between manhood and unknown universe.

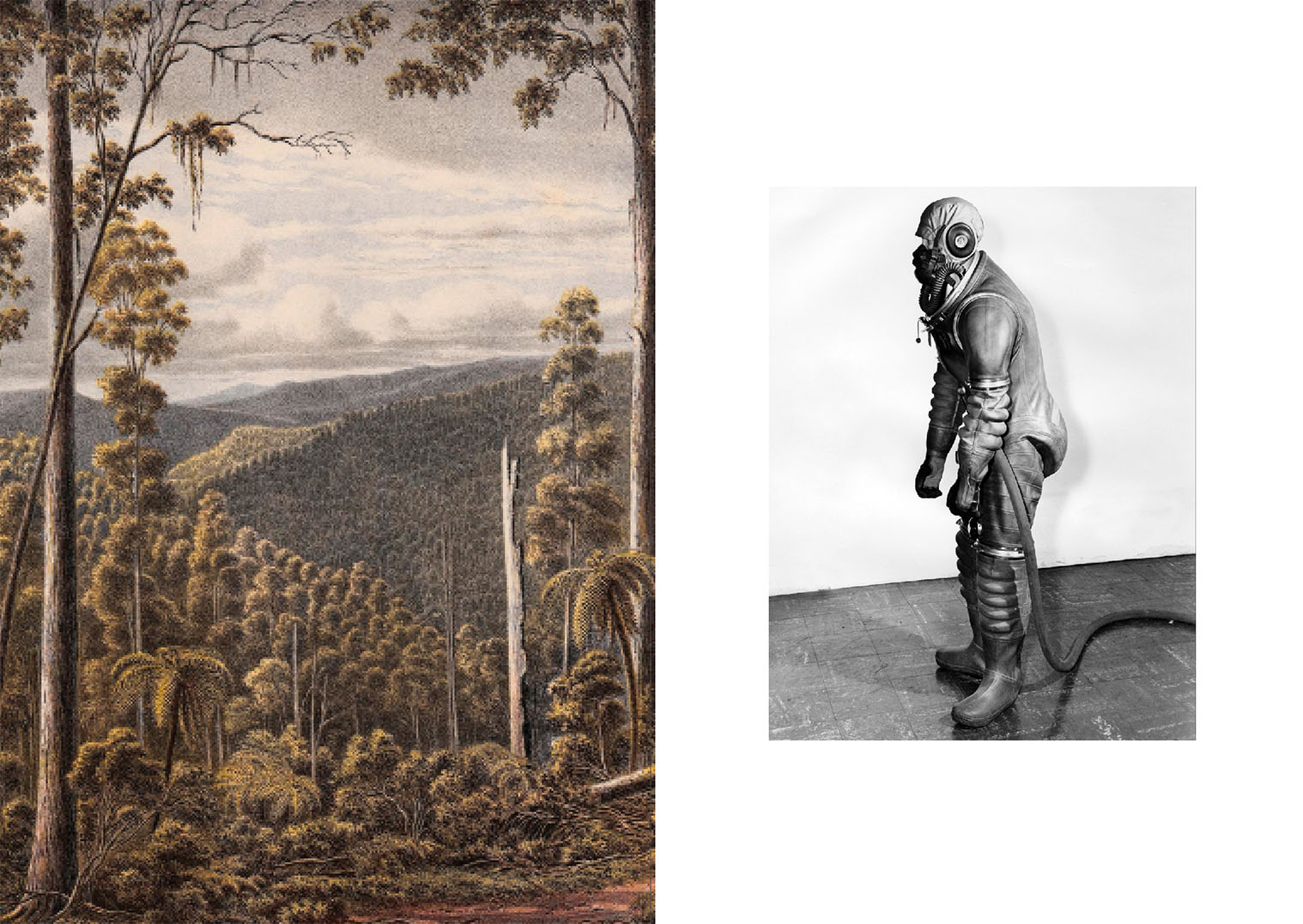

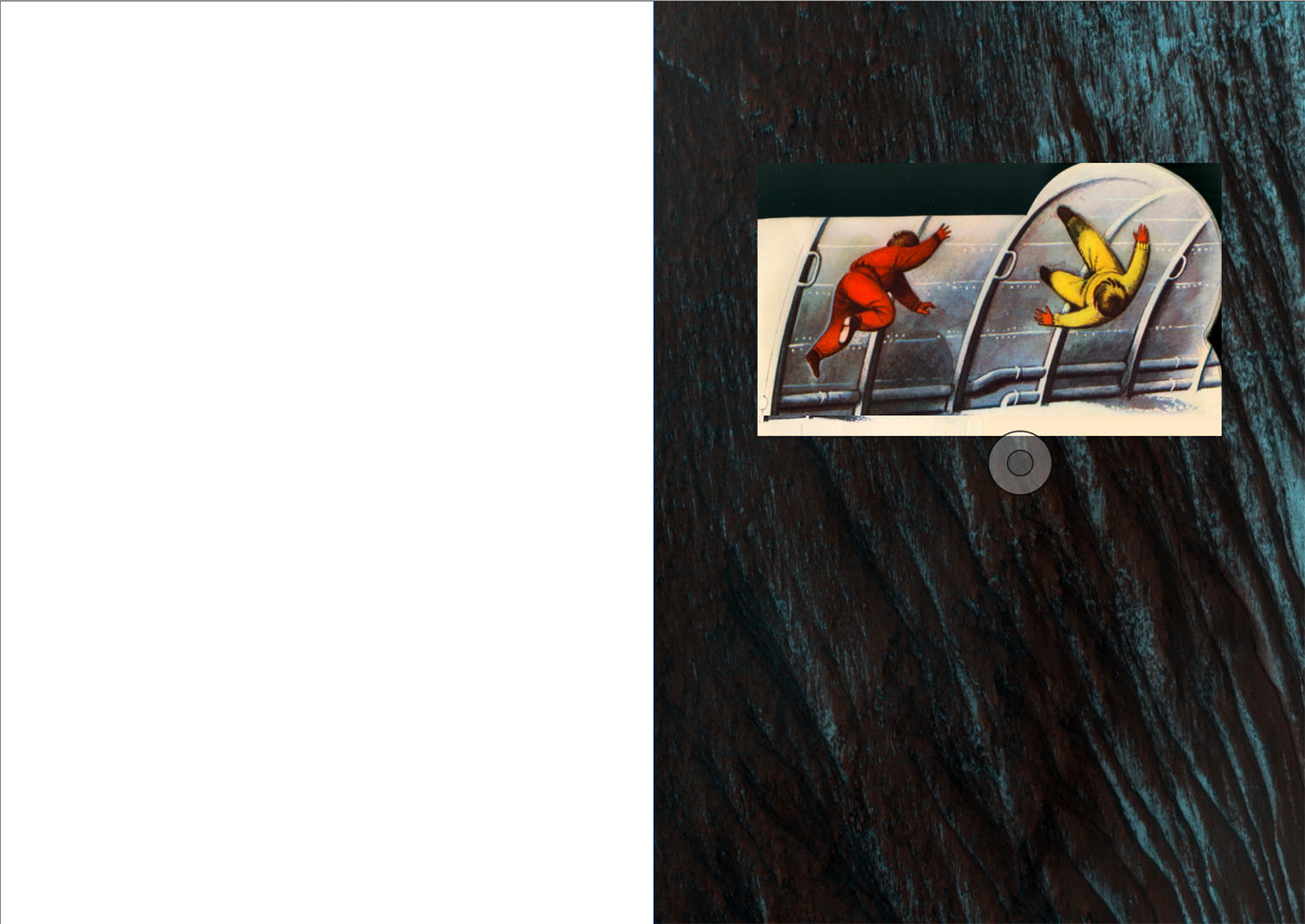

Despite the great advancements in space research and overall knowledge of the Universe, outer space is still today, as it has been in ancient times, a place of the mind’s eye where dead seas, buried civilizations, unknown inhabitants are waiting to be discovered; a place in which we are projecting mystery and charm, fear of the unknown and hope for a better future. I have edited and mounted one next to the other, according to my own emotions, images taken from different productive contexts so to underline the ambiguity of manhood relation to the Universe.

Before looking up at the sky manhood has studied, through scientific surveys, planet Earth and even then it was taken by similar emotions, such as fear of the unknow and the diverse as well as curiosity and imagination which by the end turned into the creation of million faces. Manhood has been driven both by desire of discovery and conquest and fear to see, hoping that by the act of seeing one could be dominate and defeat doubt and fear. The reader is therefore invited to became a visual explorer, to use eyes as oars in his journey through real and symbolic images. The book looks like a kaleidoscope made of photographs, graphics, images; its visual complexity might result in a feeling of confusion, similar to what one experiences whilst travelling to a foreigner country. Nevertheless those who leaf through the pages will find detailed captions and credits to the reproduced images, so that he/she might decide to autonomously start his/her own journey in the fascinating and chaos driven repository of scientific and cultural heritage of the World Wide Web.

On which fields of knowledge are you focused?

My research follows different paths and uses different media. Textiles, images and collages are the main tools I use to investigate from time to time constant aspects of man’s relationship with what has always surrounded him, be it nature, time, memory, desire, space, the basic signs of written language, the geometric patterns that follow us from the most ancient cultures. This interest necessarily leads to continuous trespassing in different disciplines, both humanistic and scientific.

What is the object of your research?

There are aspects of our existence which, beyond the social and technological transformations that we experience, are still present and untouched over the centuries, and still effect our lives. I am interested in things that may seem marginal, futile, residual but which, inevitably, still continue to be there to effect silently our lives, our feelings and our confronting the world.

Could you identify some constants in your work?

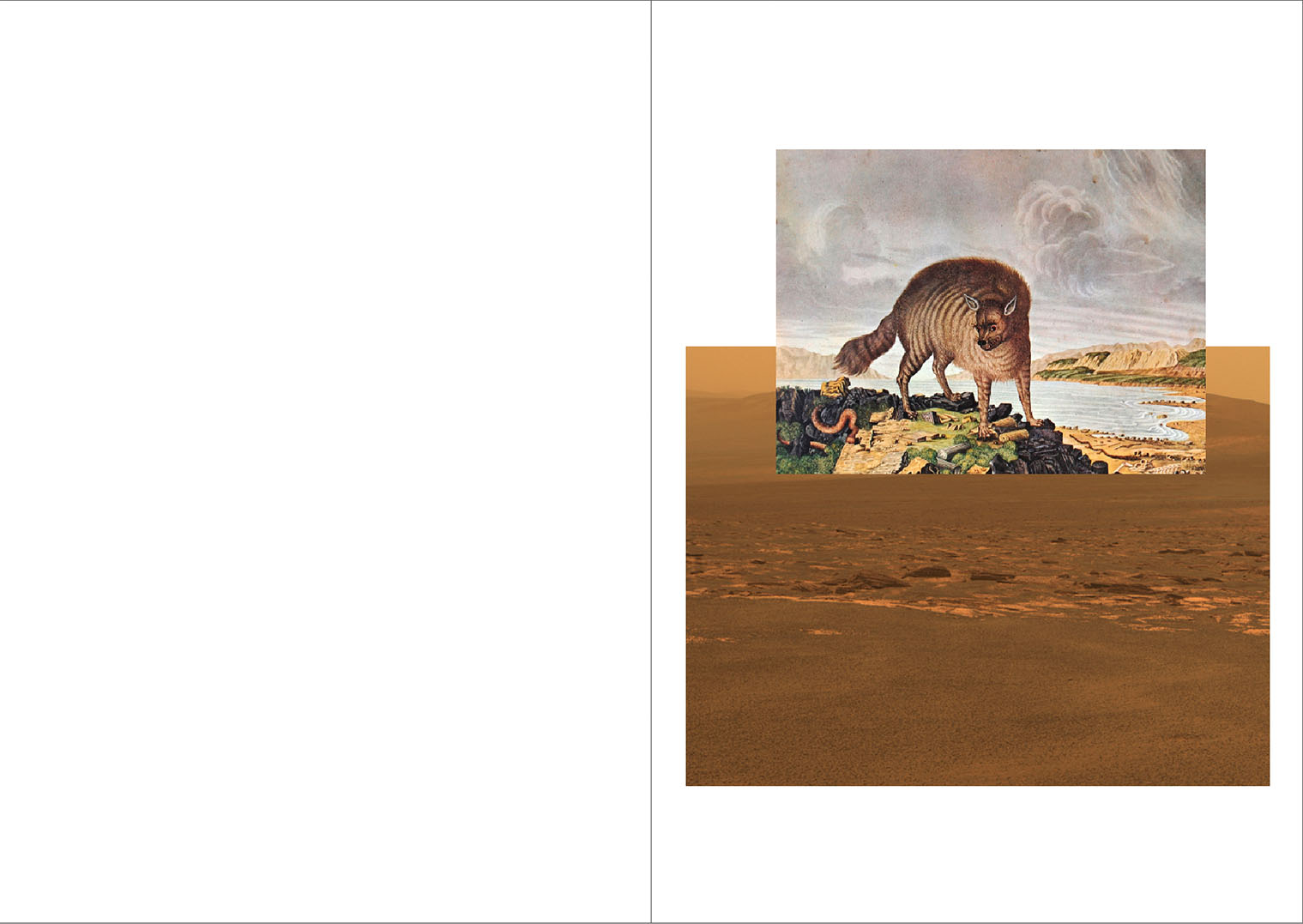

In my work one of the strongest recurrences is the use of the fragment, something left behind from a pre-existing context, which lost it either by chance or by my own intervention. The fragment is the starting point of the collage, so dear to me. Words extrapolated from a context are fragments of a lost discourse, with which I play and to which I give a new form. The single photographic image, the isolated moment frozen and torn from the flow of time is a fragment as well. Whenever we extrapolate an image from its original context, it fully shows its weakness in revealing meanings, in revealing its history. It thus becomes an ambiguous fragment halfway between past and future. With its denotative and connotative aspects, the ‘survived’ image always keeps within itself the phantom of the lost context and opens itself to other potential understandings, makes room for new visions.

My work therefore often revolves around these fragments, which I consider orphans of their original contexts so to provide them with a new narrative. My practice is therefore close to the act/idea of collecting: already existing images are the raw material that I use to question their meaning and the starting point to performe new settings and expand their meanings.

How did you find out about Aby Warburg’s work? What interests you the most?

Almost ten years ago, an enlightened curator suggested that I should read Warburg. She found it connected with my work, and she was right. The Snake Ritual fit perfectly into my interest in rituals and symbols, manifestations of a constant human need, in all eras and cultures, in the Pueblo of Warburg as well as in the Lucanian one of De Martino, trying to give meaning and order to what is unpredictable. Later on I discovered Mnemosyne BilderAtlas.

Through juxtapositions both of images and words Warburg was able to create original links between very different emotions/things; he put forward new understandings and procedures capable of crossing art history methodologies and to create unexpected connections between disciplines apparently dissimilar. He also underlined image’s psychic power.

These are the aspects of his work – as well as other authors – which resonate in my own way of proceeding.

In my book Eyes as Oars I wanted to show all sort of images – not only photographs – so to show how much they are open fields for imagination, immaterial places through which the viewer is free to surf and take time in order to locate his very own center of interest. He/she who travels through images is an explorer open to astonishments, who uses his eyes as oars (hence the title of the book) to move among systems of real and symbolic images, mixing individual fragments and mentally rearranging them into a larger entity.

How would you define an Atlas?

As a desperate attempt to put order. It inevitably arises from the act of collecting, organizing, arrange things and give them a synoptic way so that it can express a meaningful universe. A visual map that traces one possible path in chaos.

Atlas as a conceptual, formal and mnemonic device; do you use it in your work?

I collect images, especially digital ones. I don’t make distinction between photographs and illustrations, between professional and amateur photos. I save in my computer images that resonate and make me think of something, perhaps something quite different from what they reproduce. I rarely look for them on purpose. I don’t always categorize them in subject matter nor organize them or assign them a specific place, since I often have no idea what it will be of them. I know they tell me something, which could perhaps be clarified better in the future. They represent thoughts put off until later. Sometimes, in some cases after many years, those disorganized images activate new thoughts which might turn into projects or at least into ideas of projects. In this sense, my Atlas is a disorganized digital path in the chaos of my synapses and a potential work tool for future ones.

Are there visual and emotional formulas (pathosformeln) in your project?

At first, in 2012, EAO was not a book, it wasn’t even a project. It was a folder of photos of Mars, which I collected following a personal interest. Over the months I began to save in the same folder images not at all related to Space, but for me connected to the idea of space in a way that was still obscure. The result was a collection of hundreds of images; on these I began a process of slow elaboration in order to translate, understand, getting to the core and put forward a narration which had been clear to me but maybe difficult to grasps from outside. As if talking in a ciphered speech, where each image did not correspond to a single word or concept, but to a plurality of words and stories at the same time, difficult to untangle. In Eyes as Oars both scientific images and those I selected from the past, coexist so to respond to the desire to give expression to the emotional and symbolic side of man’s relationship with Space and the Unknown. For instance medieval bestiaries or mythological animals had nothing to do with Space, nor with Mars. Yet, from a symbolic point of view, I realized that for me they continued, despite their temporal and cultural distance, to act emotionally on my gaze. In this sense, the selection shows how, beyond the cultural transformations and the passage of the centuries, some of them continue to act on us, probably discharged from the original meanings, but still as vital symbols and capable of speaking to our intuition.

In your work, what is the balance between image and text?

In my work I am tied with the same intensity to images and words. Some of my works, both on paper and textiles, focus on the mark of written language and our relationship to it, transforming it into an image detached from the text. In my photographic projects, the approach is different and it changes from time to time. In Eyes as Oars, the images are presented independently, but at the end of the volume are printed the text and long explanatory captions. This is due to the very nature of the project. By quoting the sources and the original story of each image collected on the Web at the end of the volume, I am inviting the viewer to continue the visual exploration autonomously starting to whatever he/she likes. In my second book on the blue of the sky, texts are completely absent; I want here to caress an emotional and non-rational response from the viewer, and wishing that this response is totally personal and subjective, I did not consider inserting texts to accompany the images.

Thinking about Warburg’s ‘good neighborhood rule’, what are the books that underpin your project?

Cyrano de Bergerac, The Other World: Comical history of the States and Empires of the Moon, 1657

Pavel A. Florenskij, Iconostasis

Ray Bradbury, Martian Chronicles

Ovid, Metamorphoses

Isaac Asimov, Understanding Physics

Carla Rak (Rome, 1978) is an artist and photo editor who had been working many years in a photojournalistic agency. Since 2011 Rak is a freelance consultant for professional photographers and she teaches courses on photography in private institutions. Graduated in Sociology and with a PhD in Communication, her academic writings on gained the recognition of the Italian Institute of Philosophical Studies in Naples and the Cozzi Prize from the Benetton Foundation. As an artist, Carla Rak works mainly with photography, textile, collage and writing. She exhibited her works for the first time in Milan in 2015. In 2019 her book Eyes as Oars was published by Danilo Montanari. In the same year she founded her textile brand, Aprile.