Francesca Crisafulli, artist

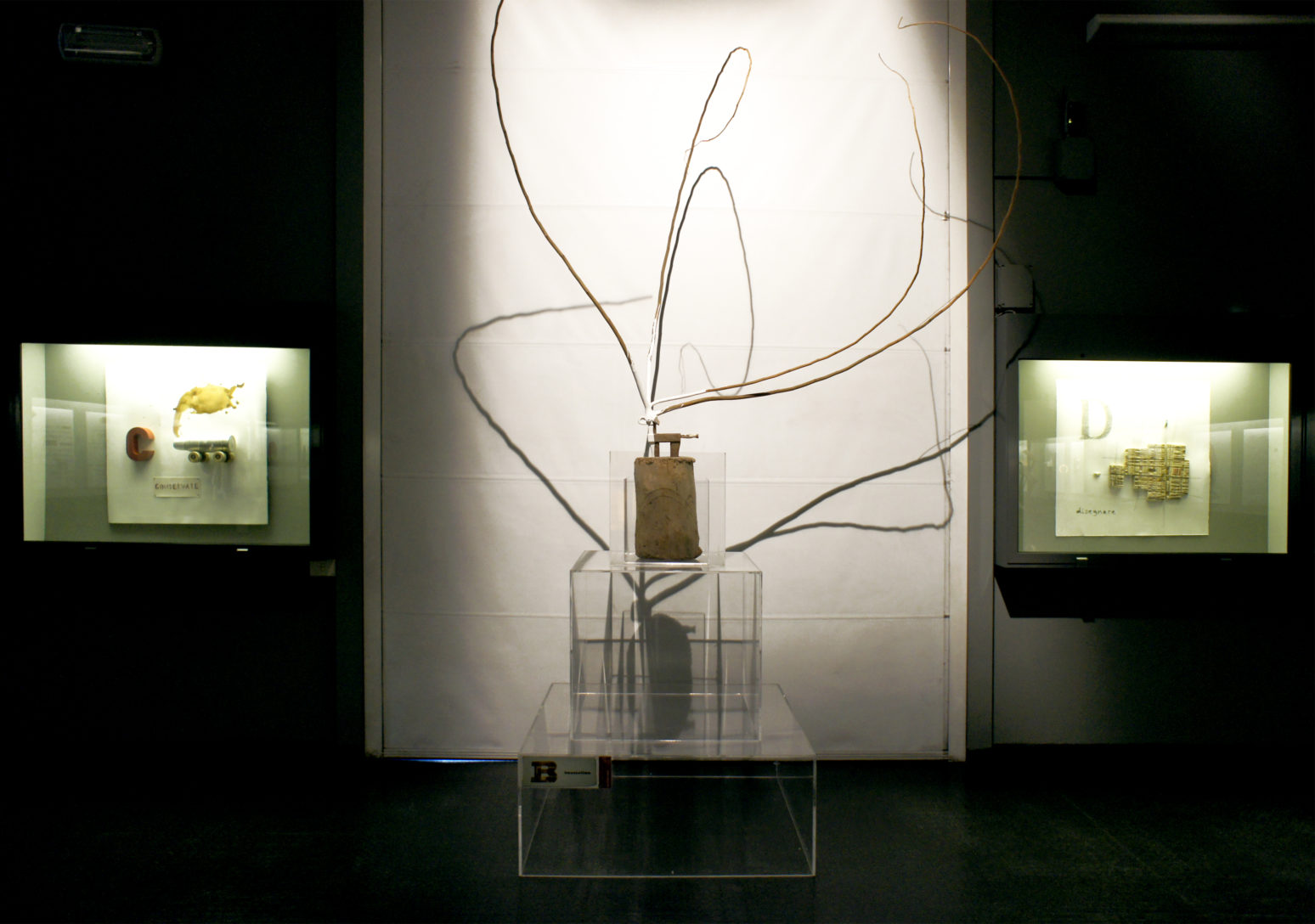

G come gioco, exhibition 2011

G as ‘Gioco’ is an exhibition shown at the Museo Nazionale delle Arti e Tradizioni Popolari in Rome and curated by Claudia Sonego in 2011.

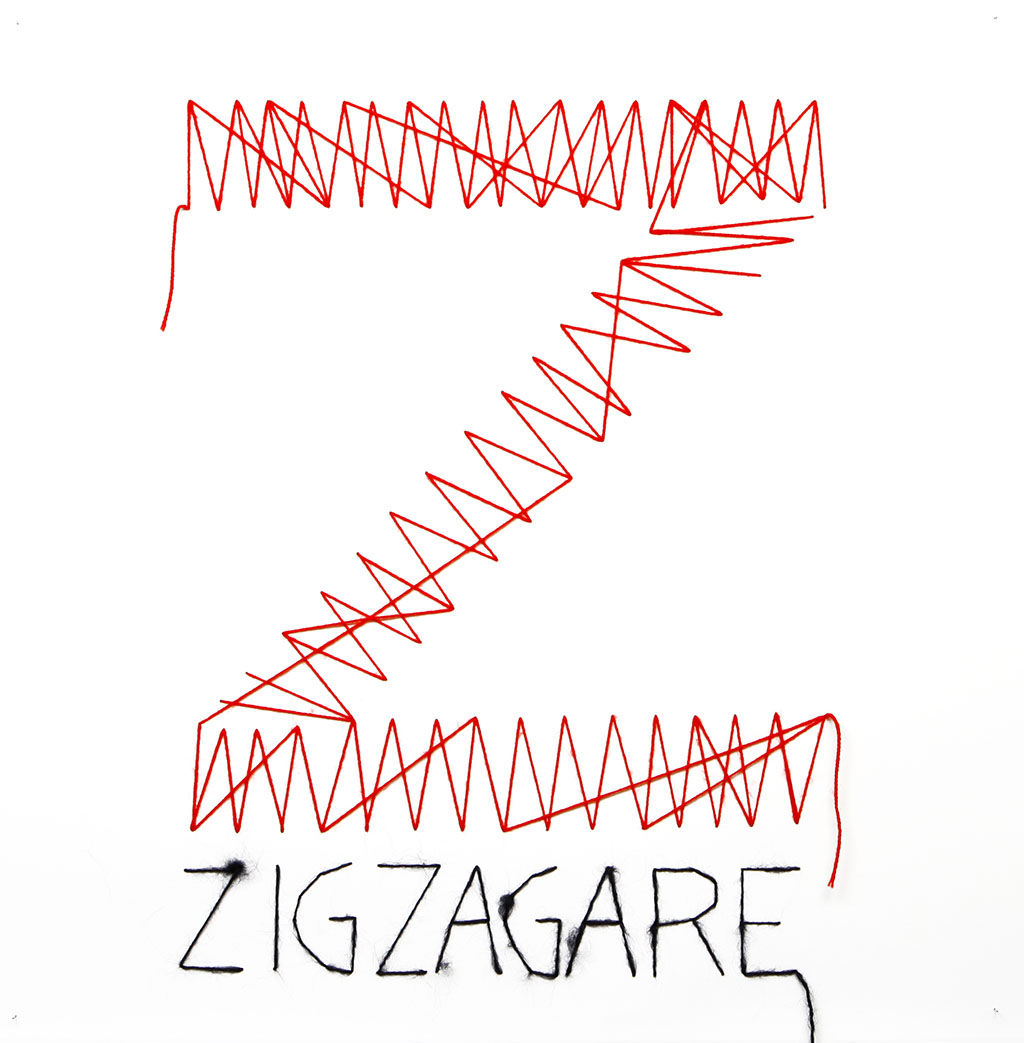

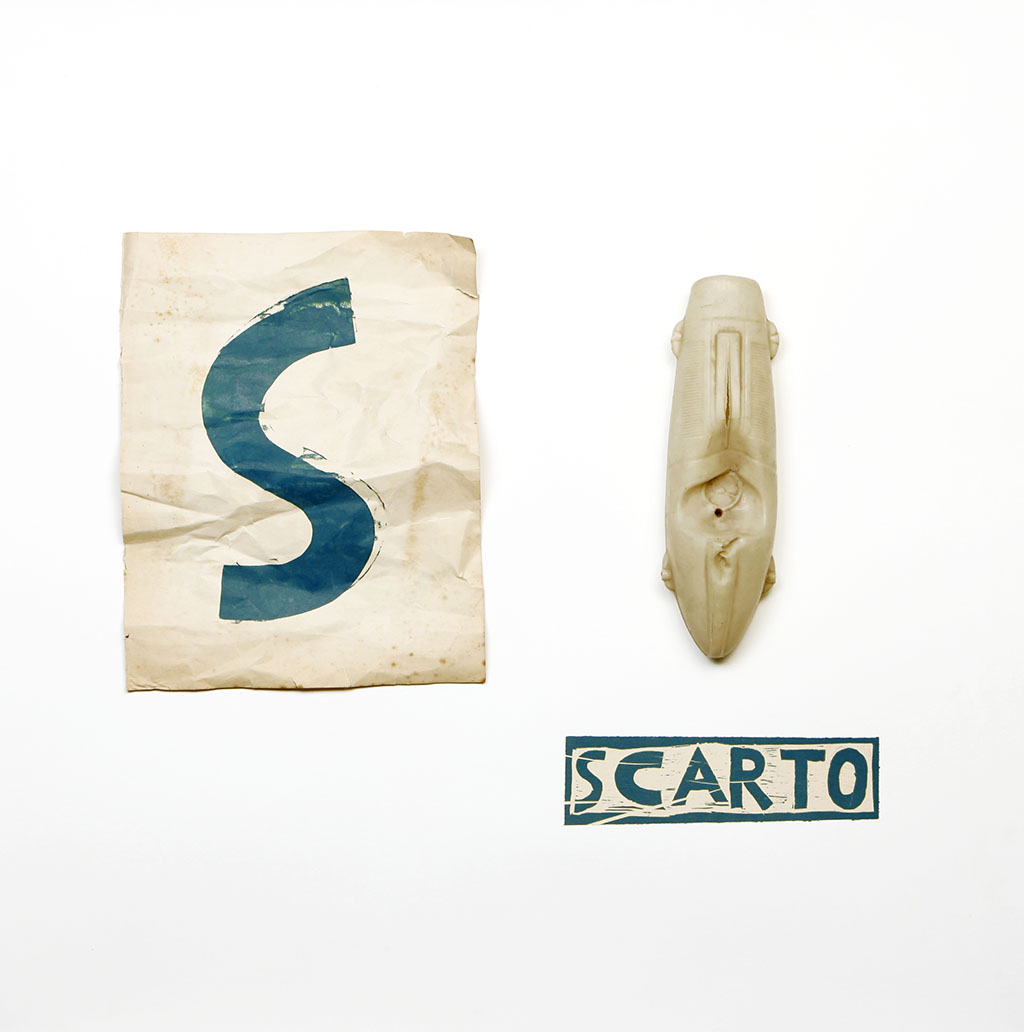

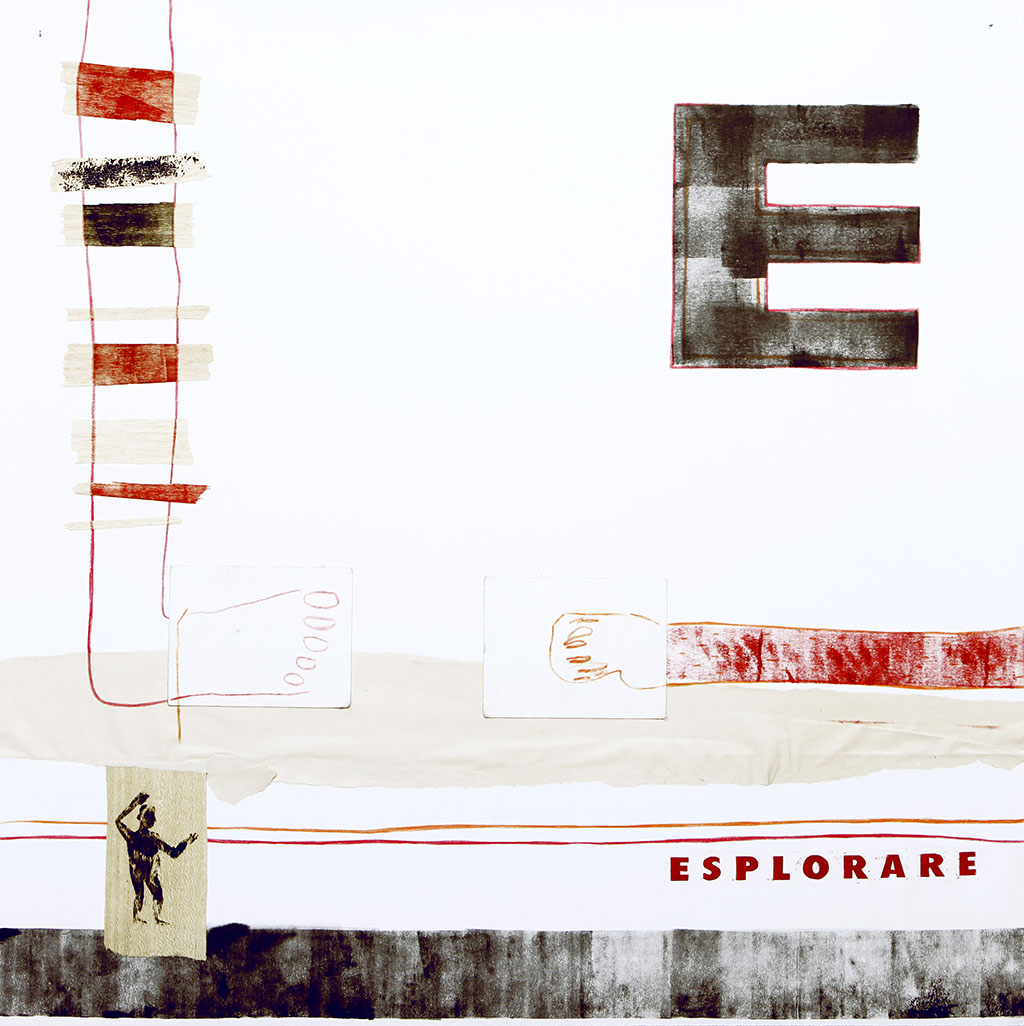

The Abecedary is the structure on which the exhibition of graphic works and sculptures is build. Twenty-six letters for twenty-six interventions based on recycling and rescuing old objects and their memory within a contemporary, and slightly ironic perspective. The site specific installations are placed along the museum spaces together with a number of small sculptures combined with graphic works each corresponding to a letter of the alphabet.

A for assembling, B for ‘bestiolina’, C for conserving, D for drawing, E for exploring … In such a way I compose an entire thematic collection with the corresponding sculpture. The recovery of materials and objects of daily uses and their re-activation respond to the Museum mission, since it engages with the very topic of the museum that hosts them. ‘Gioco’ wants to stimulate an original and engaging approach to the museum’s collections, thanks to new and inspiring mixtures and contaminations that the authors of the works are able to show, suggest or simply hint to visitors.

On which fields of knowledge are you focused?

Visual art in general, secular mysticism.

What is the object of your research?

Imperfection, traces of memory, the visual environment as a mean of intuition of other than oneself.

Could you identify some constants in your work?

The use of traces of memory left over time on objects, the assembly or the juxtaposition of pieces or images of different origins to compose a new unit.

How did you find out about Aby Warburg‘s work?

From reminiscences of my university studies in art history and from this project.

How would you define an Atlas?

An orientated collection of images.

Atlas as a conceptual, formal and mnemonic device; do you use it in your work?

Always. Our project is a form of atlas in itself, since the overall materials we use for creative purposes (woods, found objects, printed images) are stored in boxes differentiated by categories: these are totally arbitrary but functional to our purpose. The boxes are connected to each other by proximity and location, and ultimately constitute, an absolutely homogeneous mnemonic path able to widely show our creative process.

Do you know about the existence of Mnemotechnics?

Yes. I recur to it instinctively, having only visual memory!

Which mnemonic system guides the organization of your material?

The materials are filed according to shape, color, material and above all their possible future reuse.

Are there visual and emotional formulas (pathosformel) in your project?

Always and everywhere. Taking waste material and reassembling it in new forms, which carry the memory of what has already been, is the foundation of our work.

Mook reshape an imaginary object with the fragments of things whose use and origin is unknown and uncertain, as an archaeologist would do in the effort of reconstructing an entire mammoth starting from portions of bones!

The reference to child’s universe, to the game together with an ironic and unsettling reading of the present, create an emotional relationship in those who look at these “new” objects. The real and the imaginary, the present and the past mix and overlap. The use of waste material, which alone recalls a historical memory, and the playful dimension of objects connect the observer not only with his or her own often forgotten childhood world but also with the awareness of being a ” social subject”.

In your work, do you identify formal or conceptual recurrences such as repetitions and disruption, distance and proximity, identity and migration, conflict and colonization?

In our work proximity understood as a combination of different materials is always present.

In your work, what is the balance between image and text?

The image has always its own life, independent from the text (whether it’s the title of a work or the text of an illustrated book). It is never descriptive. Text and image travel on two parallel tracks that perhaps speak the same language but never meet. They feed each other by maintaining their mutual autonomies, as if, from the same balcony, they open doors to different horizons and landscapes.

Thinking about Warburg’s “good neighborhood rule”, what are the books that underpin your project?

H. Focillon, Vita delle forme, ed. Einaudi, 2002

G. Kubler, La forma del tempo, ed. Einaudi, 2002

B. Munari, Fantasia, Editori Laterza, 2006

B. Munari, Arte come mestiere, Editori Laterza, 2006

J. Berger, Sul guardare, Il Saggiatore, 2017

E. Mari, 25 modi per piantare un chiodo, Mondadori 2011

K. Couprie, A. Louchard, Tout un monde, Editions Thierry Magnier 1999

P. Cox, Coxcodex 1, Editions du Seuil 2003

AA.VV., I Quindici, vol 14°, Fare e costruire, Field Enterprises Educational Corporation 1968

P. Auster, Nel paese delle ultime cose, Einaudi 1987

Mook was founded in 2000 from a project by Carlo Nannetti and Francesca Crisafulli. Both live and work in Rome where they graduated, and today teach, at the European Institute of Design. Their artistic activity ranges from sculpture to art graphics, from illustration to design, up to the creation of workshops for children on art and recycling. Mook has exhibited in many Italian galleries and museums with solo and group exhibitions and has worked for various Italian companies.