Marta Tonelli, architect and photographer

Ėjzenštejn. Il montaggio come metodo compositivo (essay)

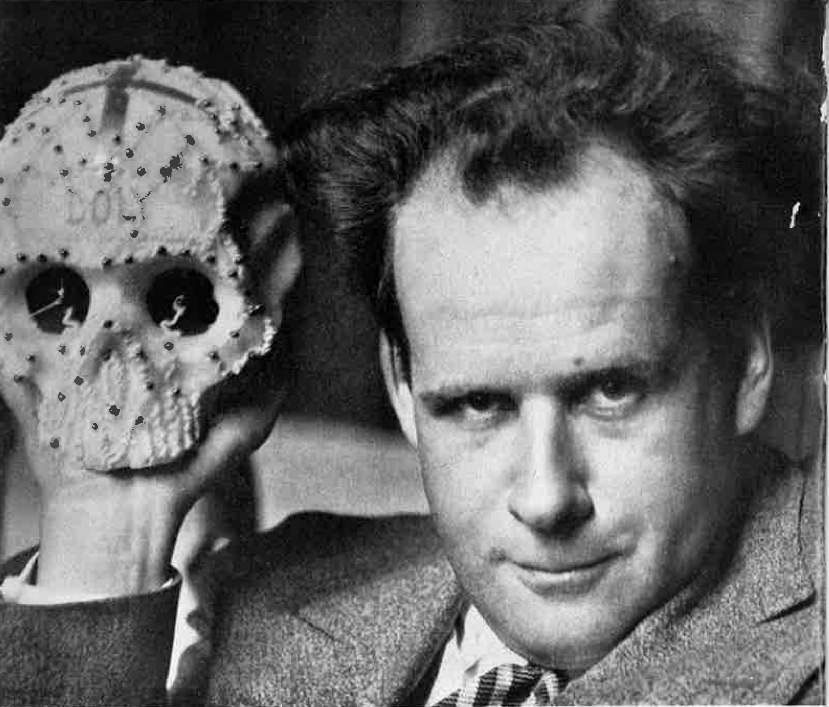

Ėjzenštejn con un teschio di zucchero

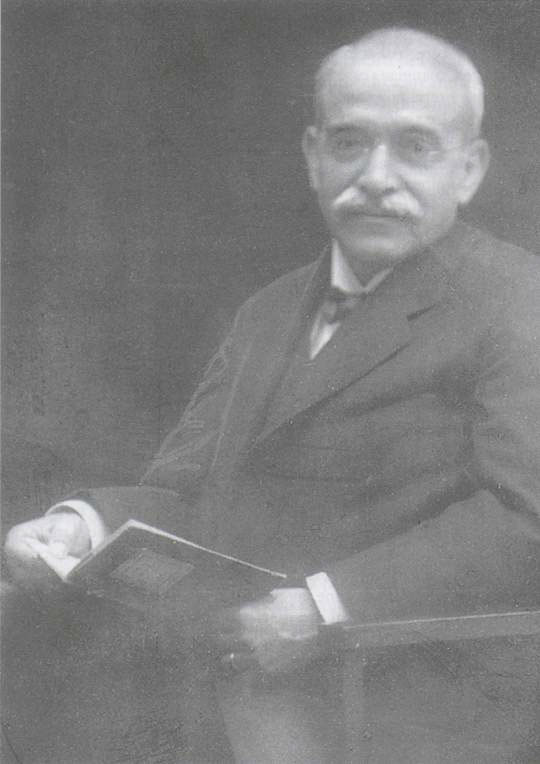

Aby Warburg nel 1929.

The Warburg Institute Archive, London.

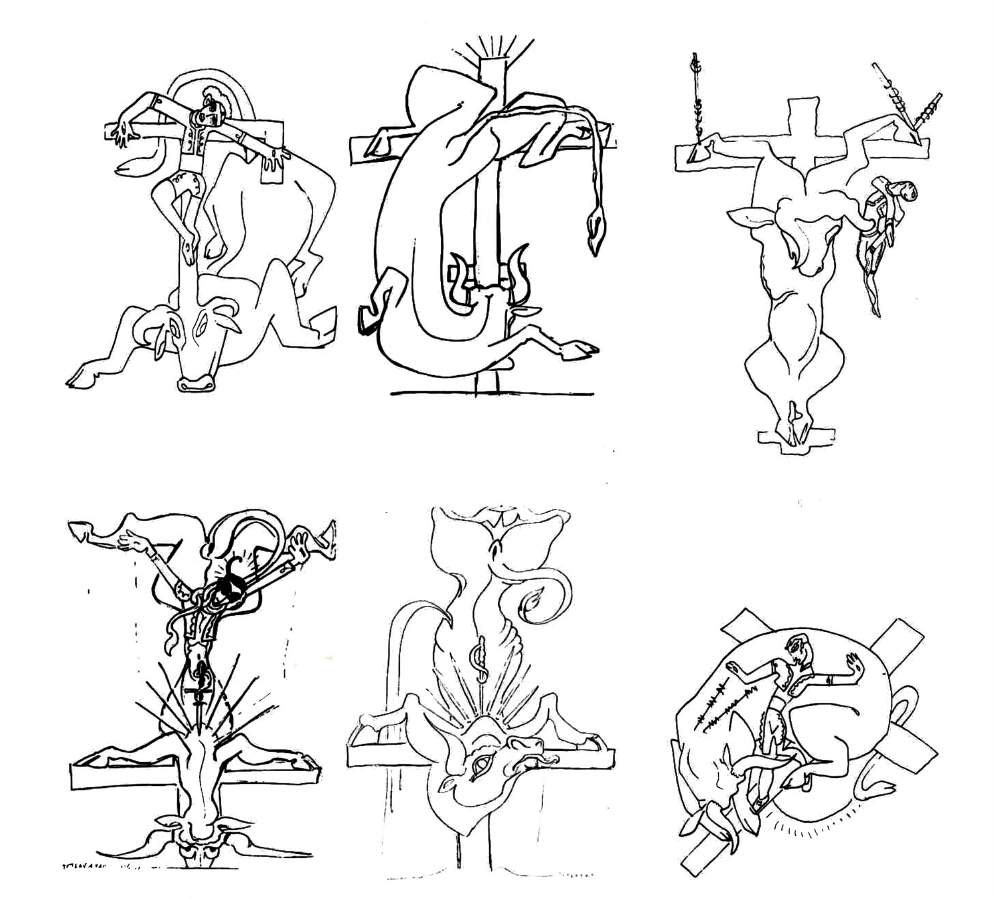

Schizzi per la suite La morte del toro

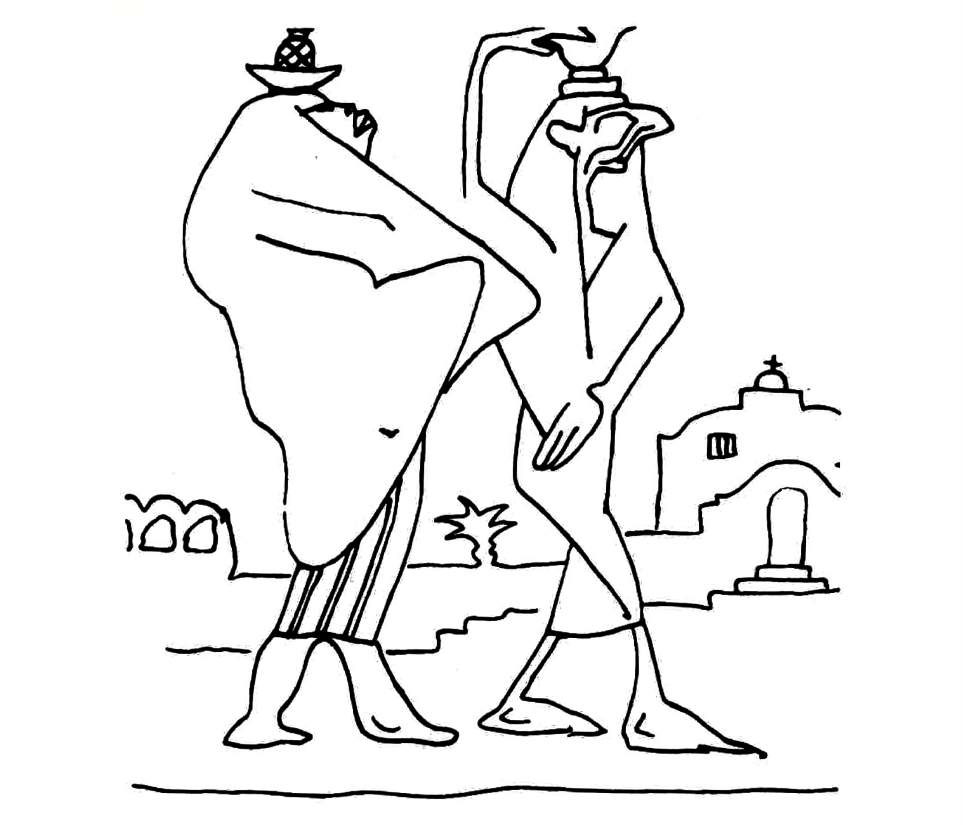

Tipizzazioni messicane.

Studi per la sequenza del mercato di Tehuantepec dell’episodio Sandunga di Que viva Mexico!

Donne messicane.

Studi per la sequenza del mercato di Tehuantepec dell’episodio Sandunga di Que viva Mexico!

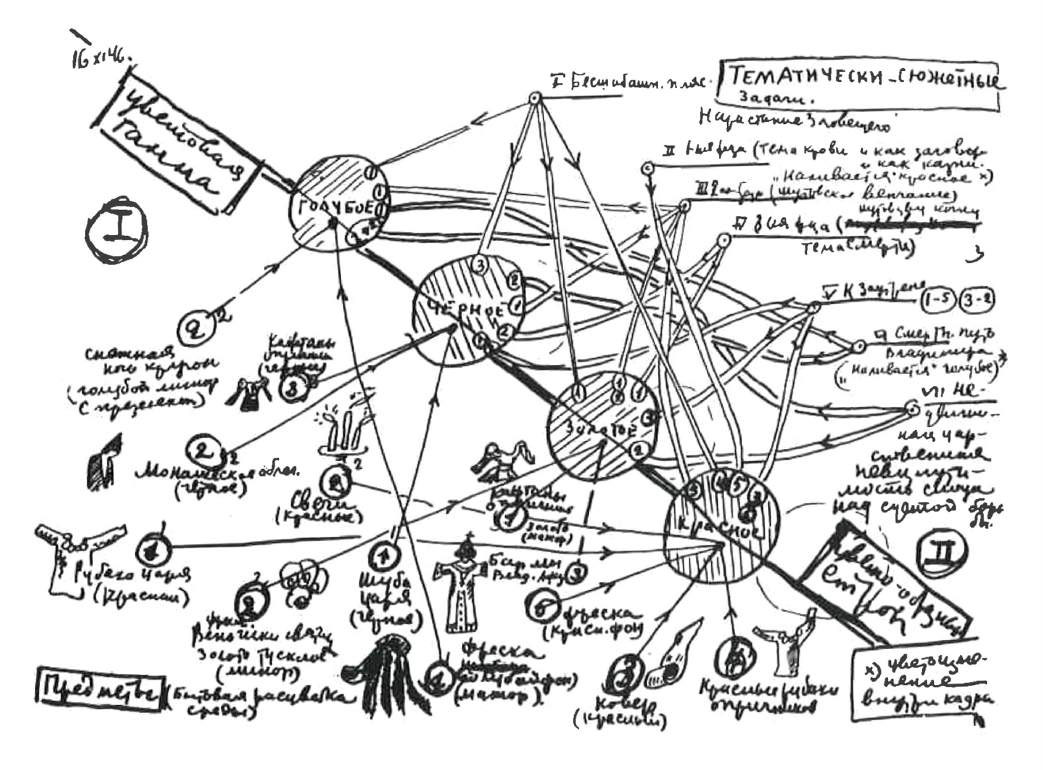

Schizzo per la sistemazione di set della sequenza a colori della congiura (16 novembre 1942). Ėjzenštejn traccia graficamente l’intero schema del percorso di Vladimir Starizki verso la morte, indicando progressivamente le variazioni cromatiche, le interazioni luministiche, i dettagli di inquadratura e i movimenti di macchina, comprese le notazioni musicali: tutti elementi che interagiscono nel montaggio verticale della sequenza eisensteiniana.

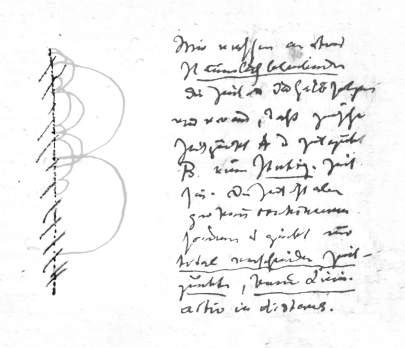

Friedrich Nietzsche, Schema dinamico del tempo, primavera 1873. Disegno a penna tratto dai Nachgelassene Fragmente. Nietzsche-Archiv, Weimar.

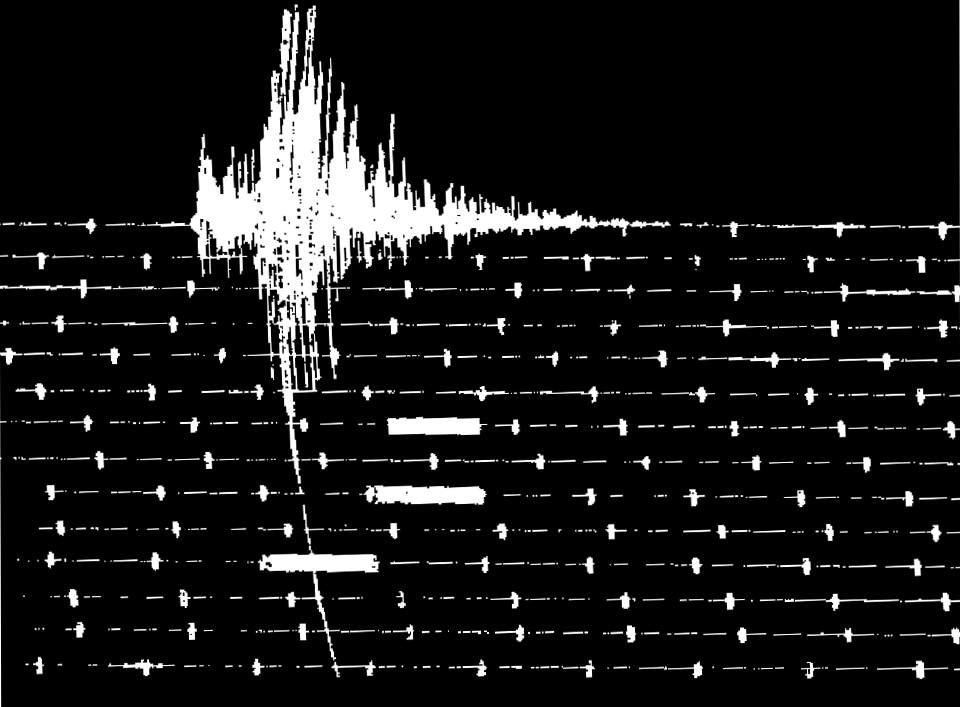

Sismogramma ottenuto con un pendolo statico di Wiechert: terremoto locale (Cile).

Da Ferdinand Montessus de Ballore, La Sismologie moderne. Les tremblements de terre, 1911

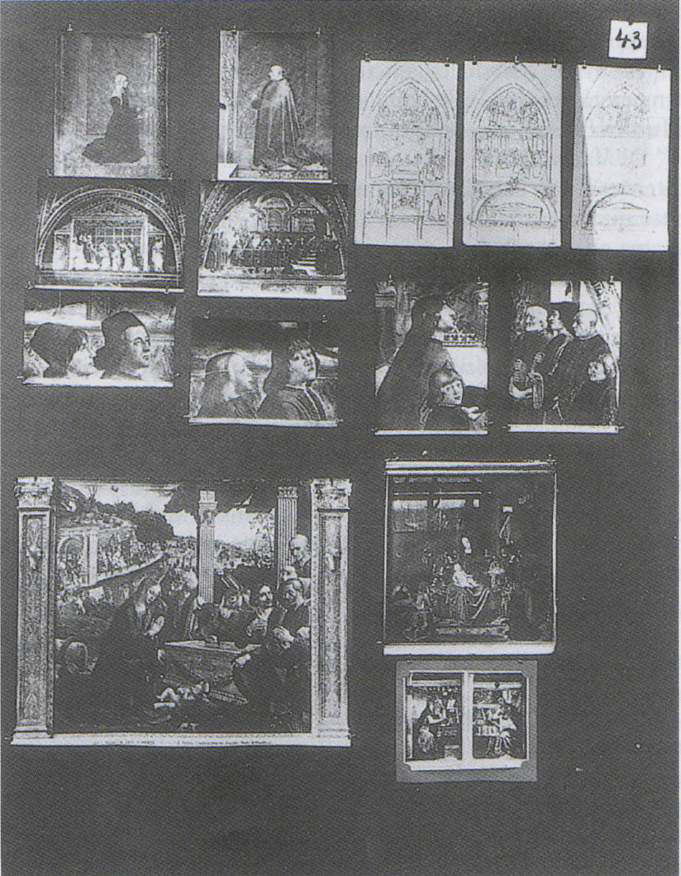

Aby Warburg, Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, 1927-29, tav. 43. The Warburg Institute Archive, London.

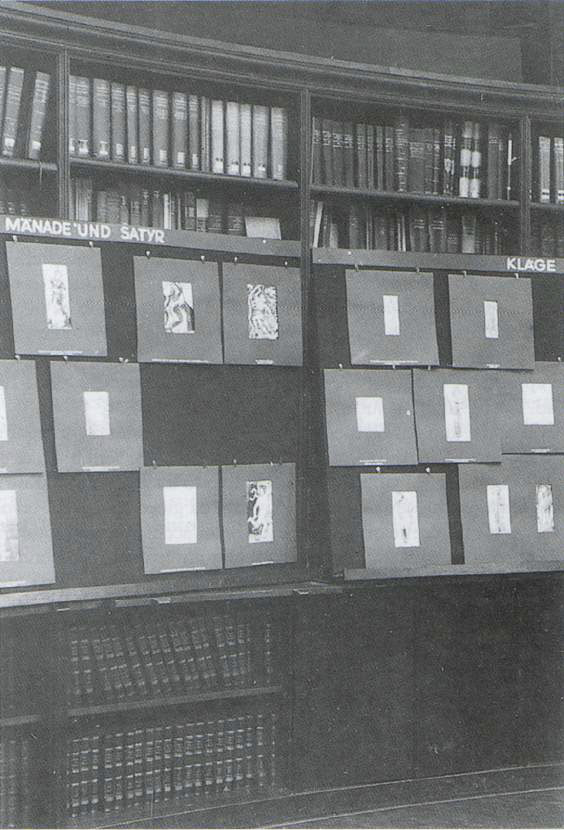

Sala di lettura della Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg di Amburgo durante la mostra Geste der Antike im Mittelalter und in der Renaissance, 1926-27. The Warburg Institute Archive, London.

Guy Girard et Michel Boujut, Cinèma cinèmas, 1987

(Jean-Luc Godard, à sa table de travail, prèparant les Historie(s) du cinéma – vidèogramme du film).

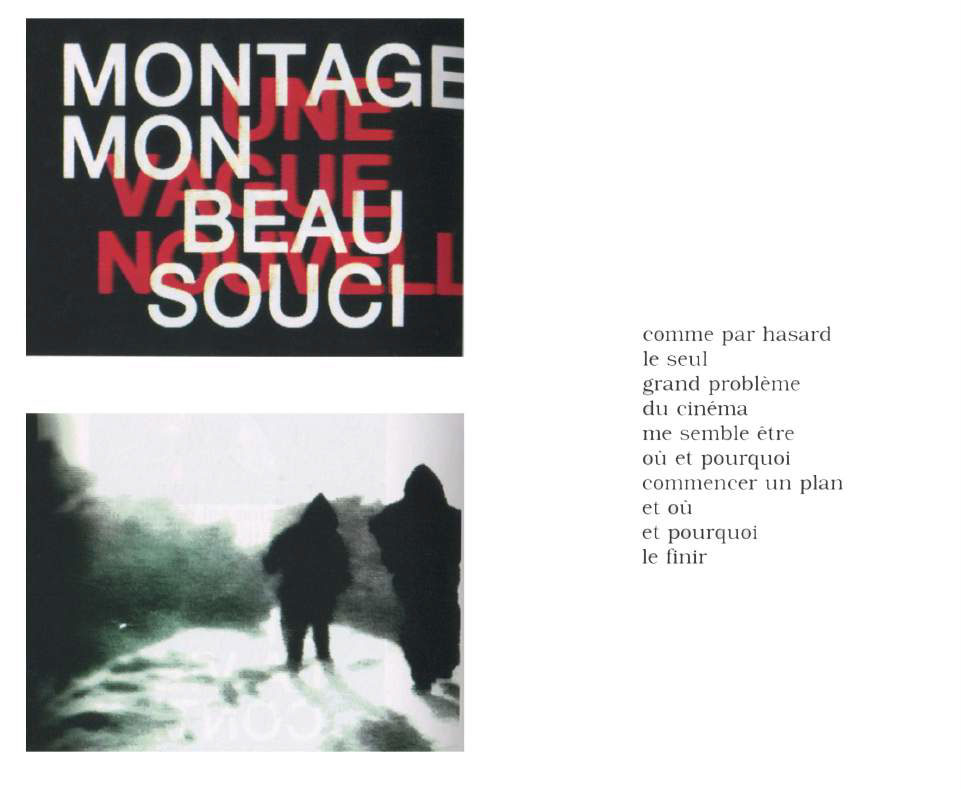

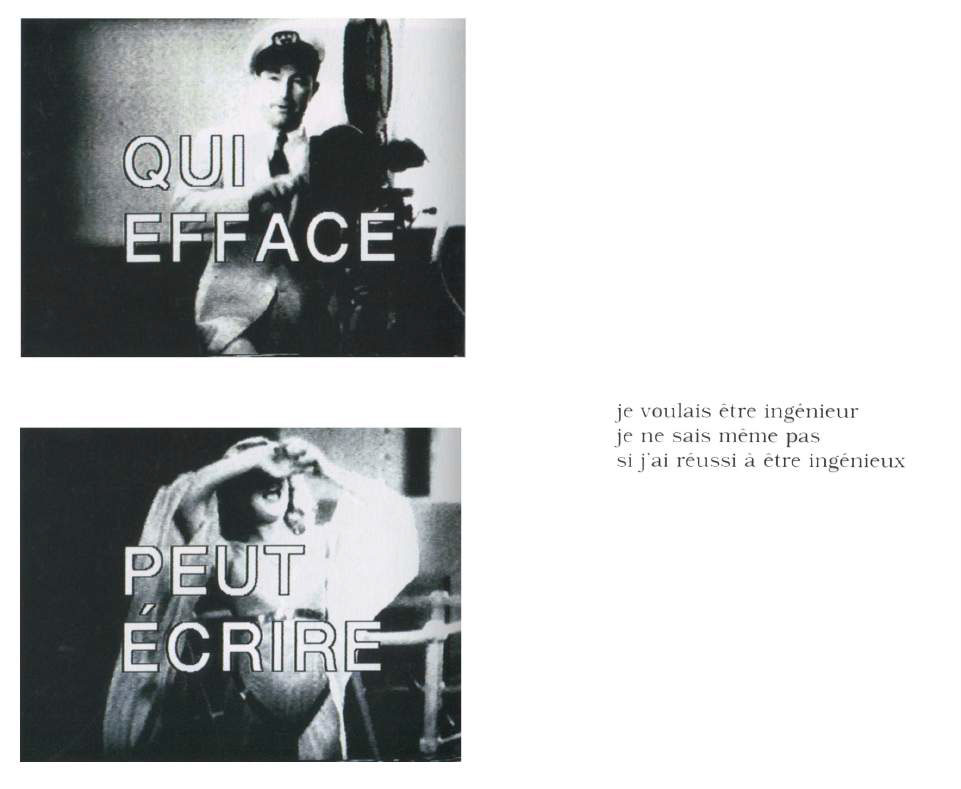

Jean Luc Godard, Histoire(s) du cinéma, Paris, Gallimard, 2006!

Jean Luc Godard, Histoire(s) du cinéma, Paris, Gallimard, 2006!

Ėjzenštejn. Il montaggio come metodo compositivo is the theoretical paper I wrote at the end of my Master in Architecture at the Accademia di Architettura in Mendrisio. The essay started from the fascination for montage as a compositional method, meant as a technique that does not belong only to cinema and it is exempt from a univocal definition. Montage is seen through two paradigmatic figures, Sergej Michajlovič Ėjzenštejn and Aby Warburg, both immersed in the research on the nature of time in relation to human sciences. The central question of the essay is what are the roles of memory and narration in the construction of History (or, for cinema, of one History)?

On which fields of knowledge are you focused?

Images and space.

What is the object of your research?

The relationship between architecture and its representation, photography as a project.

Could you identify some constants in your work?

Identifying in the past meaningful relationships for the present.

How did you find out about Aby Warburg’s work? What interests you the most?

I got closer to Warburg’s work while developing the essay on Ėjzenštejn. Warburg tries to understand and deconstruct the relationship between the present and what is primitive: by engraving the Greek term for “memory” (Mnemosyne) above the entrance of his library, Warburg suggested to the reader that he was about to enter the territory of another time. Montage has to be intended as a device that offers the visual basis of an unforeseen memory of history.

His “Atlas” is thought as a succession of boards, where rich and diverse photographic montages present heterogeneous group reproductions – Renaissance testimonies, archaeological finds, but also stamps, newspaper clippings and advertising labels. The images, printed, come from the immense collection built overtime by Warburg (already 25,000 specimens in 1929); they are fixed to wooden panels, whose base was rigorously covered with black linen sheets, through small clips – to suggest how each board in the Atlas was an agonal field, where there were not certainties but instead conflicts, frictions, changes and possibilities. To me, it is emblematic that Warburg renounces to fix images, precisely starting from the non-definitive character of the object with which he wanted to pin the photographs. Mnemosyne is a synoptic display that does not reduce nor summarize: it exposes the entire archive.

How would you define an Atlas?

As an ensemble of elements, sources, images, fascinations, linked together by logical connections, but also, where illogic has its place.

Atlas as a conceptual, formal and mnemonic device; do you use it in your work?

I build moodboards or notebooks where I try to visualize the structure of the projects and develop ideas. It serves more as a tool to look to the future than to organize the past.

Do you know about the existence of Mnemotechnics?

Yes, although I rarely practice them.

Which mnemonic system guides the organization of your material?

I am not systematic about it unfortunately, I rather have things I admire I keep going back to, things which are like pillars I keep building on.

Are there visual and emotional formulas (pathosformeln) in your project?

Yes, I would say so. There are images from a few movies, which have a structure that makes them timeless and meaningful – beyond the movie’s plot. I am thinking of the work of Roberto Rossellini, Alain Resnais, Andrej Arsen’evič Tarkovskij, Michelangelo Antonioni, Peter Greenaway, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Orson Welles, and Joseph L. Mankiewicz.

In your work, do you identify formal or conceptual recurrences such as repetitions and disruption, distance and proximity, identity and migration, conflict and colonization?

Sometimes, but not in a systematic way, nor every time.

In your work, what is the balance between image and text?

I am happy when I manage to give both to text and image their field of authonomy. This means when the text it is not meant as a caption to the image nor the image illustrates the text, but the combination of both allows for a new meanings to emerge.

Thinking about Warburg’s ‘good neighborhood rule’, what are the books that underpin your project?

Georges Didi-Huberman, L’immagine insepolta

Jean Luc Godard, Historie(s) du Cinéma

Roland Barthes, L’impero dei segni

Antonio Somaini, Ejzenštejn: il cinema, le arti, il montaggio

Lewis Baltz, The New Industrial Parks Near Irvine California

Raymond Carver, Cathedral

Are there more topics of interest that we haven’t pinned down?

The relationship between theory and practice from the perspective of Aby Warburg, but not only. The way one nurtures the other it is always an interesting question to me.

Marta Tonelli (1990) lives and works in Italy. She graduated from the Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio (Switzerland) in 2017 with Mario Botta. She has worked for the art and architecture studio Pezo von Ellrichshausen in Concepcion, Chile, and with Made in, Geneva, Switzerland. In February 2018 she started the Master in Photography at the IUAV University, in Venice. She has collaborated as research assistant and advisor with architectural historian and curator Nina Rappaport at Vertical Urban Factory, New York. She is currently resident workshop curator for the Master Iuav in Photography, Venice.